Short Summary

Scratches in a picture? Judith Roesli's carved pictures contain more than just one image and one technique. She transforms an image into a sculpture through scratching. In a conversation with art24, the artist takes us on a journey of her process and artwork.

YR: «Judith, where does the idea of scratching into pictures come from? Normally this is strictly forbidden! »

Judith Roesli: «A long time ago I was commissioned to create a greeting card for an art lover. Paper and the new box of wax colours gave me the idea to scratch a picture. At that time I scratched the figures out of the wax with a pointed kitchen knife. I enjoyed this work and the recipient appreciated the card very much. I put a copy of it in my folder of ideas. Much later, in 2018, it enticed me to work with this technique again.»

YR: «What materials do you use?»

Judith Roesli: «In the beginning I used poplar plywood as a base for my work. This wood is rather soft and is well suited for scratching. However, the boards tend to warp. Later, I chose the more stable, harder, but also heavier birch plywood. Other materials needed are acrylic binder and acrylic paint and/or coloured pencils and pigment liner, wax blocks or wax pastel and, very importantly, the etching needle, which I swapped for the scratching tool I used in the past.»

YR: «Tell us something about the creation of the works and the process.»

Judith Roesli: «Acrylic binder is used as a primer for the wooden panel. A further layer is created as a drawing using acrylic paint or coloured pencils, coloured or monochrome, depending on the scribing subject. Beeswax blocks or wax pastels form the last layer. Then the carving process begins. A slightly blunt etching needle is used to carve into the wax layer without using force, so that the needle does not damage the wood. The drawings are worked directly from memory onto the wooden panel, usually without a draft. One detail gives rise to the next, one detail grows out of the other, unstoppably. If one imagines that with one touch of the working instrument only a small dot is created, one easily gains the insight of how elaborate and decidedly time-consuming a picture is created. So far, therefore, the size of the wooden panels has remained at 30x30cm. The lines and areas freed from wax appear two-dimensional. The remaining wax areas now appear three-dimensional.»

YR: «Is there also something like a symbolic meaning for you that reveals itself in the colours? And when you "scratch away", do you have a precise idea of what structures you are scratching into the surface, or do the lines emerge intuitively and spontaneously?»

Judith Roesli: «My choice of colours is not based on symbolic meaning, although I find that very interesting. Rather, I choose the colours that fit the mood of the painting's story. But there are also paintings or sculptures where I deliberately chose non-harmonising colours during the painting process. But in the end, a pleasant play of colours always results anyway. When I make an incised picture, it depends on themes. I carve a narrative such as «It all began in the palace» (Germ: «Alles begann im Palast»). While I'm thinking up the story, I carve it (instead of writing it down) into the wax at the same time. Other incised paintings feature subjects that I have created beforehand.»

YR: «Thank you for the interview and your time. It's great to have you with art24.»

Based on Judith Roesli's carved pictures and the interview with her, art24 has set out on the trail of this method. The so-called grattage thereby shows in an obtrusive way the boundlessness of art. So, in the first part you will learn how Judith Roesli works and where the technique comes from.

Note: Technical terms are shown in italics the first time they are mentioned and explained in a glossary at the end of the text.

Judith Roesli's Working Process of Scratching

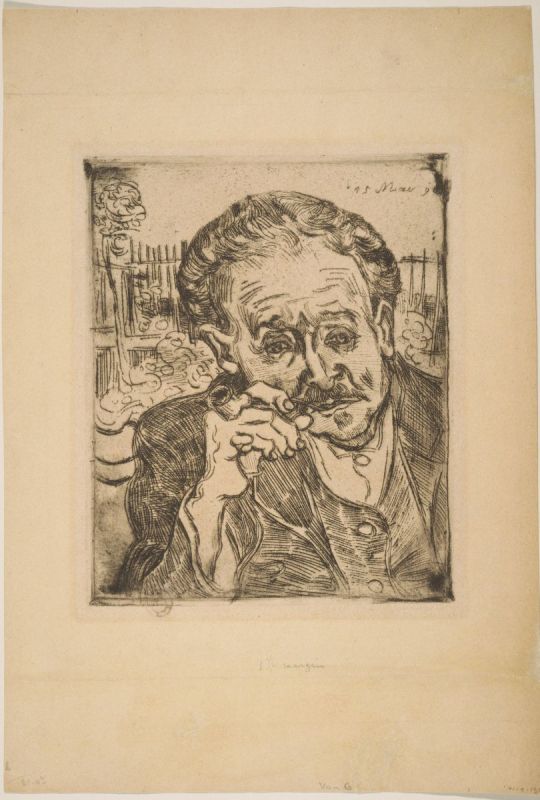

At first glance, the way Judith Roesli scratches her pictures is mainly known from graphic work techniques, for example, the scratching of a representation into a zinc plate by means of a needle. By scratching into the smooth surface of the printing plate, the work gains depth. The resulting indentations are then filled with ink. The remaining ink is then wiped off again, a sheet and the scratched printing plate are run through a printing press together and the artist receives a first (drypoint) etching version. Depending on the depth of the carved furrows and lines, different intensities of ink are left on the paper, which give life to the image.

But this graphic process is not what characterises Judith Roesli's works. For she penetrates layer by layer through colours that have already been applied, thus exposing what lies deeper. Her carved images are also not duplicated, as is done with the templates of the prints. Her method can rather be compared to sculpture. The sculptor usually has an idea in mind at the beginning and begins to remove the material by sketching on the stone. Little by little, what is «hidden» in the stone becomes visible and thus also the vision and history behind the artistic creation. Judith Roesli's works can thus be described as a sculptural transformation process - the two-dimensional painting becomes a three-dimensional object by means of a sculptural process.

First, the artist applies paint to the wooden surface, similar to the primer on a canvas. After the base coat has dried, another painted layer is added. This layering already foreshadows the next working step. As in plastic arts, a mass, here the paint, is applied first, which remains flat for the time being and is not shaped. Now an opposite transformation to the application takes place: the layered colours are removed again. And this is where the artist Judith Roesli changes from being a paintress to becoming a sculptress. In this way, she reveals in one and the same work what is literally hidden inside it; and this not only in the sense of a metaphorical or two-dimensional dimension, which in painting usually creates an illusion of space and body. No, the depth in the picture, which is gained through the removal, opens up a third dimension: the picture becomes a sculpture, which contains an actual spatial and physical level and can therefore no longer be described as pure painting, which only creates an illusion of space and body.

The Grattage technique and its «Inventor» Max Ernst

The «inventor» of this scratching technique, the so-called grattage (from French «gratter» = «to scrape off»), was the German Expressionist Max Ernst. In this process, developed especially for oil painting and derived from frottage (from French «frotter» = «to rub off»), superimposed layers of painting are removed, creating new colours and forms. To do this, Ernst placed objects such as string, metal mesh or coarse fabric under the canvas, which he pressed against it to make the respective shape and texture visible on the canvas (cf. Newman 2018, pp. 15-16). Through this combination of frottage and painting over with at least two layers of paint (cf. Newman 2018, pp. 9-10), Ernst was able to transfer imprints of real forms onto the painting surface and created a relief-like structure and depth in the canvas. In doing so, a real, existing trace of something became embedded on the canvas. Ernst then scratched off the layers of paint so that the colours underneath became visible again. The scratchings thus left another pattern, which was defined by the respective depth, on the one hand by the layers of paint, on the other hand by the relief-like frottage imprints, as well as by the colour patterns appearing underneath. Ernst thus produced three-dimensionality on a flat surface through a combination of different techniques; through the frottage, through the layers of painting and through the removal of the paint. Significant for this technique is his work «The Whole City» (Germ. «Die ganze Stadt») from 1935/36, in which he pursued his fascination for the forest and for the Romantic movement.

«Max Ernst laid his canvas over various objects with raised textures – pieces of wood and string, grates, textured glass panes – and, drawing the paint over them with a palette knife, brought forth the most vivid effect.» (Spies 1991, S. 148)

Ernst thus experimented with unusual patterns and forms on the surface of the canvas by means of the grattage. In this way, he succeeded in transforming his compositions into something new and mystical through the surprising structures that were revealed. At the same time, however, these structures also referred to something familiar, because the reference to something that actually existed automatically created a lively impression. On the one hand, the works were abstracted, but on the other hand, patterns and especially the colours, which were initially still hidden under the top layer of paint, came into focus and thus the alienated, abstracted element became something alive again. The colour carried something organic and a symbolic power with it. This symbolic meaning of colour and its relationship to nature interested Max Ernst (cf. Wilhelm 2020, p. 23). The grattage offered him the opportunity to deal with colours. The textures of the objects and the underlying colours inspired him to see things that he associated with nature, but which also represented the unconscious and those things that deviated from the norm. In Max Ernst's work, then, the given textures and levels define the work. Despite the conscious action and decision-making, i.e., through the act of selecting and recombining the scribes or the objects, the grattage at the same time allowed him space for the unconscious in his working process, in which he could follow his intuition, for example in the scribing itself or in which he was inspired by the unexpected structures of the prints.

Find out more about the technique of scratching in part 2 of the blog

Glossary Part 1:

(Drypoint) Etching: Etching is a graphic technique of intaglio printing used in printmaking. It involves carving dots or lines on a smooth surface using an etching needle. In drypoint etching, a needle made of hard steel is used directly on the printing plate. The plate is usually made of copper, zinc, brass or iron.

Author: Yvonne Roos