Carved Pictures Part 2 - Art as a Field of Possibility

Paul Klee Uses the Grattage for a Prehistoric Recollection

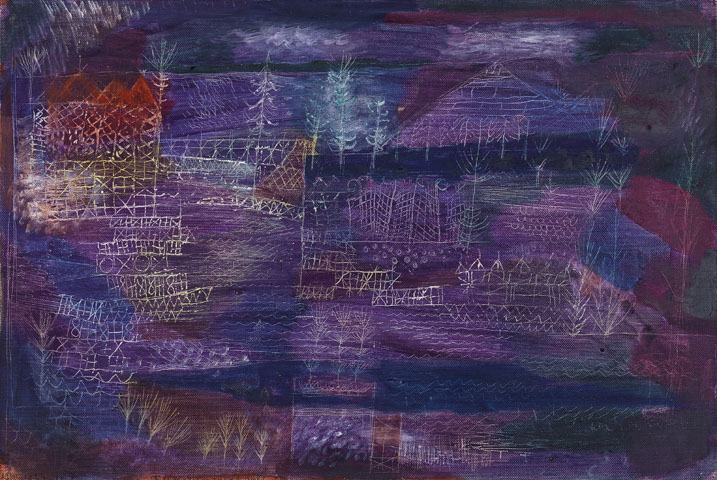

Alongside Max Ernst, Paul Klee is another artist who brought the technique of carving to the profession. Klee's incised drawings show parallels to prehistoric drawings that were scratched, scraped or pierced into stone (so-called petroglyphs). Parallels to Judith Roesli's incised drawings can also be seen. They both refer to something primal that is inherent in any modern human form of expression. Klee used thick paste colour and then scratched the drawing into the colour layer with the help of a suitable object (cf. Zentrum Paul Klee, p. 18). In this way he also shows what is in his works. What was built up with several layers of paint is exposed by the scratching and – as with Roesli – allows completely new works to emerge.

In addition, the technique can also be seen as an analogy to the human psyche and inner life. Klee dealt reflectively with different subjects (cf. Zentrum Paul Klee, p. 19). And as an avant-garde artist, he was also interested in reduction/abstraction and wanted to depict the «essential» accordingly. For him, this was reflected in lines. That is why the prehistoric works mentioned at the beginning were of particular interest to him. These often depicted highly reduced people, animals and objects, as well as abstract ornaments (cf. Zentrum Paul Klee, p. 21). There is something timeless and primordial about the line; it conveys the desire for human expression that has been passed down through generations and was already developed in prehistoric times with the means available. For example, the drawings on the rock walls of the Combarelles cave in the Dordogne (cf. Kraal 2020, p. 5). In Klee's work, too – as in Roesli's – the boundaries between abstract signs and those charged with meaning are not fixed but fluid (cf. Zentrum Paul Klee, p. 23). The scratching away of the surface can thus, in addition to the relief-like and sculptural process, also be understood as working with lines, which makes the essential visible.

Judith Roesli's Imaginative Carved Pictures

Thus, through scratching, new forms are carved out of the existing. The underlying structures play a decisive role in determining this new form of expression. Painting over, as well as scratching off and uncovering, is an act of selecting and recombining a multitude of alternatives (cf. Ubl 2013, p. 149). In the scratch paintings, the flatness of the canvas is disturbed, even destroyed. The picture is dynamised by the different layers and is thereby reminiscent of reliefs, stucco works and sgraffito. These are all art techniques that are often described as an intermediate form of painting and sculpture and which, due to their three-dimensionality and the play between flatness and depth, create light and shadow effects. These effects of three-dimensionality fundamentally determine and shape the works. They breathe life and plasticity into them. Starting with painting, it suddenly becomes multifaceted, flexible and departs from the idea of a purely two-dimensional representation on a flat surface. Sculpture and painting suddenly move very close together. Judith Roesli's approach takes up this effect, which Max Ernst and Paul Klee also knew how to use. Random traces are left in the work and produce new colour structures and forms. In a similar way, she explored the surface of the material on the vehicle of the painting. She uses the randomness to inspire herself and discover things or shapes (in it). In a similar way to Ernst and Klee:

«The goal was to let one’s unconscious mind find patterns within the textures to make objects and creatures appear. As if finding shapes in the clouds or within the grain of wood, Ernst discovered new nature-oriented forms in the process.» (Newman 2018, S. 17)

In Roesli's case, the selected ones leave an inspiring process. Thus, painting undergoes a metamorphosis: from a flat application of paint, inherent with the possibility of illusion, the surface changed to an object appearing three-dimensional, which not only creates three-dimensionality through an illusionistic effect.

Max Ernst was particularly influenced by the Surrealist movement, the discussion about the unconscious and psychoanalysis. Grattage and frottage were invented by him to promote an «automated technique»; the unconscious, which is always in danger of narrowly escaping, was to be captured and find expression in art. (cf. Newman 2018, p. 21). There is always a tension between different levels in Ernst's (semi-)automatic procedures, which can also be observed in Judith Roesli's work. In both, there is a distinction between the real and the imaginary, between an interior and exterior, variables that developed as a result of deliberation and rational decision-making (cf. Newman 2018, p. 23). Thus, imagined contents can be seen, but they also refer to real sources of inspiration, such as vegetal motifs, but also materiality itself. The interior and exterior are therefore to be understood in two ways. A cognitive/spiritual inside that influences the work, something is exposed, while at the same time it is influenced by the external conditions and has to act within a certain framework, for instance conditioned by the materiality, its reaction and the technique. But it also means the various layers in the work itself that mirror this process and that carry something to the outside or leave it hidden inside when only certain places are scratched.

This transformation and metamorphosis of the material evoke various memories of processes for Ernst and Roesli. For example, perception in dream-like states, changes in the natural world, but also transitions from states of mind and spirit. In Ernst's case, the abstracted representations obviously stimulate the mind so that the purely rational is erased. In Judith Roesli's work, the patterns even seem to have an ornamental function, as they appear, for example, in sacred, medieval manuscripts, which are thereby supposed to produce a contemplative stimulation and immersion. In the process, something cosmological, inexplicable and dream-like is visualised, which is contained in the world but always surrounded by something inaccessible and inexplicable. In the process, surprising things unfold that captivate and trigger inner movement and calm with simultaneous restlessness. This is the case, for example, with the patterns, animal and human figures, figures and plant motifs in Roesli's work «Everything began in the palace» (Germ. «Alles begann im Palast»). Colours emerge and stimulate the imagination, allowing interpretations to flow forth. And at the same time, there is a familiarity in it that we know from our everyday lives, from fairy tales and from stories. Roesli also plays with language. Her picture titles direct our thoughts to these already known and newly invented fairy tales and stories and make us think about them further.

Both Roesli and Ernst also dissolve the relationship between form and structure and recombine them. In doing so, they depart from various normative notions related to our seeing and our culturally learned understanding of art. Consequently, it also departs from traditional notions of what painting is and what sculpture is, even though these notions have basically already been «broken through» in past art traditions. For example, medieval stucco work, which was often painted but at the same time stood out in relief. Roesli continues this break with the imagination. The process of transformation is given by the carving into the material. In the process, something is inscribed/carved into it that challenges us to recognise something new and to question our way of seeing. In Roesli's work, as in Ernst's, we are encouraged to immerse ourselves in the work and surrender ourselves to it. At the same time, the process of thinking and understanding about what is depicted is also stimulated, which always has something irrational inherent in it, just like the working process itself. Everything seems to be held in a momentary state, a process of transformation. For inherent in the grattage is a potential and obvious possibility of change, which can thus be discovered in the artistic processes of Roesli, Klee and Ernst. The carving technique is a reflection of artistic activity and further development, but also of the content of the painting. The materiality is destroyed in order to be immediately reshaped - and with it the context. The destruction reveals underlying structures and compositions that surprise and stun.

Carved Paintings as a Mimesis of Natures Processes

As already mentioned, the multi-layered nature of the images is brought to the fore through the scratching. The work and its materiality thus become part of the essential. This is evident in the form of lines and surfaces, but also in the topology and layering of the material. This layering of material establishes a parallel to naturally occurring layers, sediments and erosions of the earth, drawings that are created in nature, so to speak. Art takes on these natural processes and mimics construction and destruction. Thus, nature is no longer merely imitated in its superficial appearance, but a mimesis of natural processes also takes place. In the process, only part of what lies beneath is ever revealed, whereas, as in the incised pictures, there is basically an infinite number of possible combinations of showing or concealing. The grattage also shows many things and at the same time contains a mysterious pictorial potential that remains hidden from us. Max Ernst, Paul Klee and Judith Roesli play(ed) with darkness and brightness, with the tactile and the optical, with looking in and looking at, between a possible transparency and the opaque through this layering (cf. Ubl 2004, p. 82). But the temporality of the process is also visualised in the incised images. In the end, it is not a single simultaneous experience that is shown, but a past seeing, a future seeing and a non-simultaneous seeing. For the gaze will never be able to perceive everything, the world and its works of art will always harbour a secret within themselves (cf. Ubl 2004, p. 7).

You can read the artist interview with Judith Roesli and the first part of the discussion about the Grattage here.

Glossary Part 2:

Mimesis: The word comes from the ancient Greek and means «imitation». The term, coined by Plato and Aristotle, has various meanings for the arts and is always to be understood in a historical context. Mimesis of nature refers to living forms and organisms and thus also refers to their beauty and the relationship of representation to the world, i.e., reality. Thus, not only a «dead», exact copy of the visible should be produced, but the living should be realised and represented through the painting process. The work is thus not only a copy, but itself becomes a created nature (natura naturata). By means of abstract, but also concrete art, a new reality was created, whereby the depictive character of art was also questioned and whether it can also make something visible that is not visible (Paul Klee).

Relief: The earliest reliefs come from the cave art of the Upper Palaeolithic. Reliefs were also carved into megaliths from the Neolithic period. Relief (from the Italian «rilievo» = «elevation») is a form of design that stands out plastically from a flat background. A distinction is made between «low relief» (e.g., sgraffito), «half relief» and «high relief». In addition, there are also «sunken reliefs», which were worked into the surface as a hollow form. Almost anything can be used as a material, e.g., wood, stone, gold, iron, etc. Reliefs can be produced in different ways, for example by casting, forging, engraving or embossing. Since the relief has contact with the background plate, i.e., does not stand free like a sculpture, it is not called a sculpture, although it is worked plastically. As a result, relief is often described as a sculptural technique that approaches the flatness of painting.

Sgraffito: Sgraffito (Ital. «sgraffiare» or «graffiare», = «to scratch»), is a technique used on wall surfaces. After different colours of plaster layers have been applied, the upper layers are worked on by scratching them off in such a way that the layers underneath are exposed again. This creates an image or decorative pattern. Sgraffito is considered a stucco technique.

Stucco work: Stucco, from the Italian «stucco» for «piece» or also «plaster» and is a form of design in which material is applied to a surface in order to form sculptural elements from it, for example on walls, ceilings or vaults. The material used is building mortar or gypsum plaster. Stucco work was already made in early advanced civilisations. In antiquity, they were used to decorate interiors and facades.

picture credits:

cover_It all began in the palace, close-up. Judith Roesli. Oil pastel. Photo: Judith Roesli.

Image 1_ the Man with the Pipe (Portrait of Dr Paul Gachet). Vincent Willem van Gogh, 1890, etching on wove paper, sheet: 31.6 x 21.6 cm, photo: Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Image 2_ It all began in the palace, close-up. Judith Roesli. Oil pastel. Photo: Judith Roesli.

Image 3_ It all began in the palace, close-up. Judith Roesli. Oil pastel. Photo: Judith Roesli.

Image 5_ It all began in the palace, close-up. Judith Roesli. Oil pastel. Photo: Judith Roesli.

Image 6_ Les Combarelles. Engraved head of a horse, ca. 18,000-11,000 BC, 40 cm, Photo: ARTSTOR_103_41822003849591, University of California, San Diego

Image 7_ River landscape. Paul Klee, 1924. oil paint on canvas embossed paper (brush and needle edged with gouache and pen and ink, on cardboard, 36 cm x 53.7 cm, Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe.