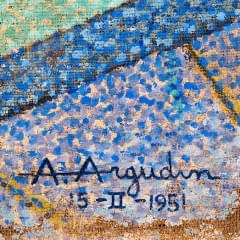

Antonio Argudín

né(e) le 1910 à Havana

Style artistique

À propos

Antonio Argudín, 1910 in Havanna geboren, besuchte dort die Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas San Alejandro und war als Maler, Bildhauer und Grafiker in Kuba tätig. Ab 1935 stellte er regelmässig aus, so etwa mehrmals im Círculo de Bellas Artes in Havanna. Von 1953 bis 1954 war er Mitglied der Grupo de Afirmación y Divulgación del Arte Cubano (GADAC) und nahm 1954 und 1956 an der Bienal Hispanoamericana de Arte in Havanna und Barcelona teil.

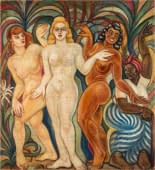

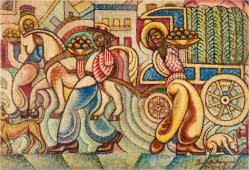

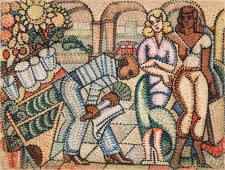

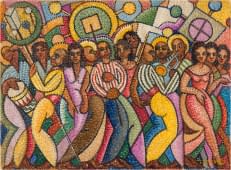

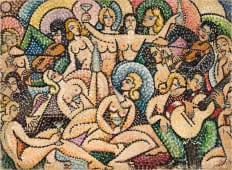

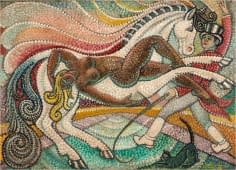

Argudíns Werke zeigen mehrere Parallelen zu avantgardistischen europäischen Stilrichtungen. Sein Verzicht auf einen perspektivischen Bildraum, die Auflösung der geschlossenen Körperlichkeit von Dingen und die künstlerische Reduzierung eines Objektes auf geometrische Formen sind allesamt charakteristische Darstellungspostulate des Kubismus. Der durchkomponierte geometrische Bildaufbau und der Pinselduktus bestehend aus Punkten hingegen, verweisen auf die Stilrichtung des Pointillismus. In der Art und Weise wie Argudín Bewegungsabläufe und Dynamik durch versetzte Repetition des sich bewegenden Bildinhaltes malerisch festhielt, bezieht er sich auf die italienische Schule des Futurismus.

Die Anfänge einer modernen Kunst waren in Kuba ebenso wie in anderen Ländern Lateinamerikas eng mit der nationalen Identitätsfindung verbunden. So begann sich in Kuba eine Kunsttradition auszubilden, die tradierte Formensprachen aus dem Ausland übernahm, sich aber zugleich auf ihre afrokubanischen Wurzeln und ihre nationale Kultur besann. Diese, der kubanischen Kunst eigenen, Synthese wird ebenfalls in den Werken Antonio Argudíns ersichtlich, der um 1950 in europäisch avantgardistischer Manier kubanische Sujets auf die Leinwand brachte. Argudín malte lebhaft musizierende Kubaner, Früchteverkäufer und freudig tanzende Figuren.

Antonio Argudín was born in Havana, Cuba in 1910, where he attended the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas San Alejandro and worked as a painter, sculptor and graphic artist. From 1935 and onwards he held regular exhibitions, frequently at the Círculo de Bellas Artes in Havana. From 1953 to 1954, he was a member of the Grupo de Afirmación y Divulgación del Arte Cubano (GADAC) and participated in the Bienal Hispanoamericana de Arte in Havana and Barcelona in 1954 and 1956.

Argudín's works show several parallels to avant-garde European styles. His renunciation of a perspective pictorial space, the dissolution of the closed physicality of things, and the artistic reduction of an object to geometric figures are all characteristic representational postulates of Cubism. On the other hand, the composed geometric structure of the image and the brushstroke consisting of dots and dashes refer to the style of Pointillism. The way in which Argudín captures motion sequences and dynamics through staggered repetition of the moving image content, is his way of referencing the Italian school of Futurism.

The beginnings of modern art in Cuba, with similarities found in other Latin American countries, were closely linked to the search for national identity. Thus, an artistic tradition began to develop in Cuba that adopted traditional formal languages from abroad, but at the same time adhered to its Afro-Cuban roots and its national culture. This synthesis, particular to Cuban art, is also evident in the works of Antonio Argudín, who, around 1950, portrayed Cuban subjects on canvas in a European avant-garde manner. Argudín painted lively Cubans playing music, bustling fruit merchants and joyously dancing figures. Argudín, accordingly, evokes the image of a cheerful pre-revolutionary Cuban civil society, which, given the repressive measures prevalent at the time, points to a transfigured representation that is out of touch with reality. Lacking substantiated information concerning the artist’s political leanings at the time, leaves room for interpretation as to Argudín's possible subversive intentions. Argudín's works are clearly situated in a politically turbulent era, which inevitably had an impact on the production of that art. Argudín's oeuvre is thereby not only an important testimony to the changeful Cuban history of the mid-20th century, but also the expression of an incipient avant-garde art movement in Cuba.

Argudíns Werke zeigen mehrere Parallelen zu avantgardistischen europäischen Stilrichtungen. Sein Verzicht auf einen perspektivischen Bildraum, die Auflösung der geschlossenen Körperlichkeit von Dingen und die künstlerische Reduzierung eines Objektes auf geometrische Formen sind allesamt charakteristische Darstellungspostulate des Kubismus. Der durchkomponierte geometrische Bildaufbau und der Pinselduktus bestehend aus Punkten hingegen, verweisen auf die Stilrichtung des Pointillismus. In der Art und Weise wie Argudín Bewegungsabläufe und Dynamik durch versetzte Repetition des sich bewegenden Bildinhaltes malerisch festhielt, bezieht er sich auf die italienische Schule des Futurismus.

Die Anfänge einer modernen Kunst waren in Kuba ebenso wie in anderen Ländern Lateinamerikas eng mit der nationalen Identitätsfindung verbunden. So begann sich in Kuba eine Kunsttradition auszubilden, die tradierte Formensprachen aus dem Ausland übernahm, sich aber zugleich auf ihre afrokubanischen Wurzeln und ihre nationale Kultur besann. Diese, der kubanischen Kunst eigenen, Synthese wird ebenfalls in den Werken Antonio Argudíns ersichtlich, der um 1950 in europäisch avantgardistischer Manier kubanische Sujets auf die Leinwand brachte. Argudín malte lebhaft musizierende Kubaner, Früchteverkäufer und freudig tanzende Figuren.

Antonio Argudín was born in Havana, Cuba in 1910, where he attended the Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas San Alejandro and worked as a painter, sculptor and graphic artist. From 1935 and onwards he held regular exhibitions, frequently at the Círculo de Bellas Artes in Havana. From 1953 to 1954, he was a member of the Grupo de Afirmación y Divulgación del Arte Cubano (GADAC) and participated in the Bienal Hispanoamericana de Arte in Havana and Barcelona in 1954 and 1956.

Argudín's works show several parallels to avant-garde European styles. His renunciation of a perspective pictorial space, the dissolution of the closed physicality of things, and the artistic reduction of an object to geometric figures are all characteristic representational postulates of Cubism. On the other hand, the composed geometric structure of the image and the brushstroke consisting of dots and dashes refer to the style of Pointillism. The way in which Argudín captures motion sequences and dynamics through staggered repetition of the moving image content, is his way of referencing the Italian school of Futurism.

The beginnings of modern art in Cuba, with similarities found in other Latin American countries, were closely linked to the search for national identity. Thus, an artistic tradition began to develop in Cuba that adopted traditional formal languages from abroad, but at the same time adhered to its Afro-Cuban roots and its national culture. This synthesis, particular to Cuban art, is also evident in the works of Antonio Argudín, who, around 1950, portrayed Cuban subjects on canvas in a European avant-garde manner. Argudín painted lively Cubans playing music, bustling fruit merchants and joyously dancing figures. Argudín, accordingly, evokes the image of a cheerful pre-revolutionary Cuban civil society, which, given the repressive measures prevalent at the time, points to a transfigured representation that is out of touch with reality. Lacking substantiated information concerning the artist’s political leanings at the time, leaves room for interpretation as to Argudín's possible subversive intentions. Argudín's works are clearly situated in a politically turbulent era, which inevitably had an impact on the production of that art. Argudín's oeuvre is thereby not only an important testimony to the changeful Cuban history of the mid-20th century, but also the expression of an incipient avant-garde art movement in Cuba.