Following the traces of #1 Ch. A. Mangin

In the context of the first "Following the traces of" blog post, precisely such an artist is to be introduced. He identifies himself neither through a Wikipedia article nor through a long and extensively researched curriculum vitae with high-ranking places of education, an international exhibition list or with great, celebrated achievements, but convinces the viewer solely through his characteristic oil painting.

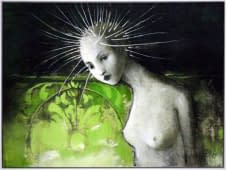

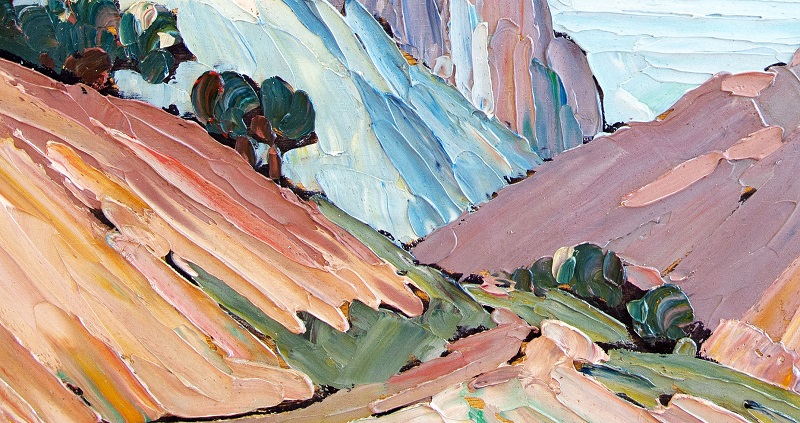

At first glance, the landscape paintings of the French artist Ch. A. Mangin may seem rather "ordinary". They are a small part of the many expressive works that were created in the same period of the early 20th century. At first sight, many people probably think that these are "nice" pictures of coastal landscapes and ancient buildings. However, if you take not just one but a few steps closer to the works and let the painting technique take effect on you, you will immediately notice the special technical characteristics of the oil paintings: The rich supple colour used, the radiant tonal palette, the deliberate, powerful expressive execution, the surfaces, some of which are very smooth and some of which are very structured by the brushwork (Figure 1).

On further admiration, one discovers even more: an apparently monotonous shade consists of many different colours. The pink colour, for example, is composed of the tones yellow, red and white, and sometimes there is also a green underneath (Figure 2).

But who is this impressive artist who captivates the viewer with his painting style alone? Who is the person behind "Ch. A. Mangin"? And what surprises are hidden in rather inconspicuous works of art? We will get to the bottom of these questions.

Sujet and Dating

Mangin was an artist of travels. His works live from what he saw on his travels, motifs that touched him, impressed him and inspired him to paint them.

He painted mainly landscapes, deserted beaches, coasts, village and town streets, buildings, monuments, gardens and temples. Only rarely are a few inhabitants or small groups of figures to be discovered in the shadows of the streets.

The selected paintings, which were created between 1929 and 1934, can be divided into three country-specific themes: France, Syria and Africa.

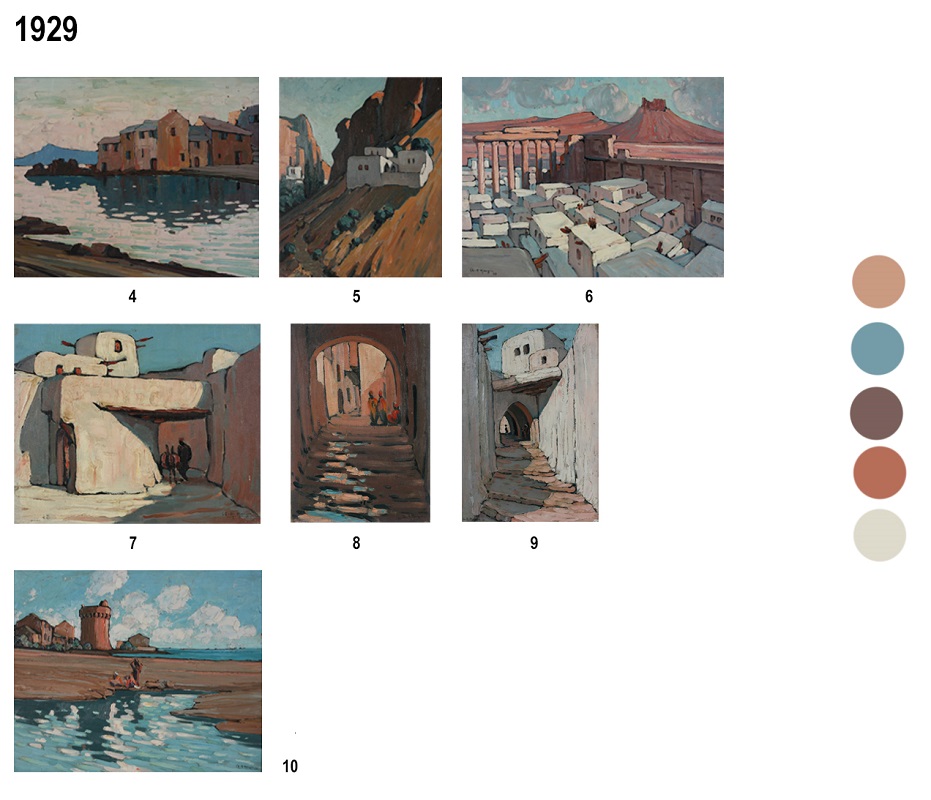

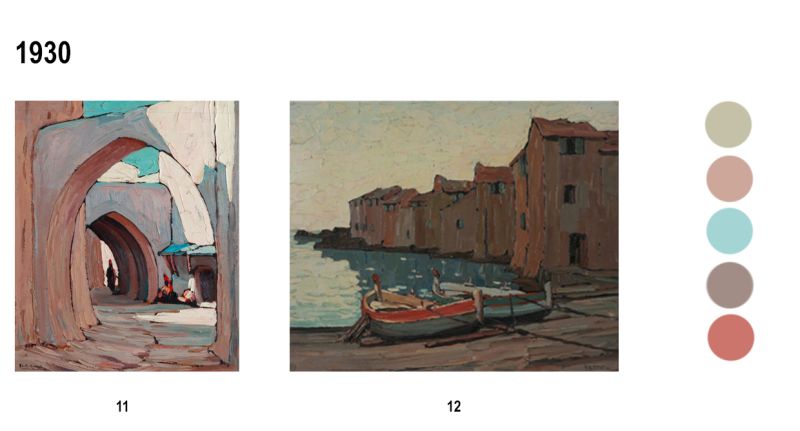

In 1929 and the early 1930s, the French artist travelled to the coast of France and Syria. A few years later, he stayed on the western coast of North Africa (Figure 3).

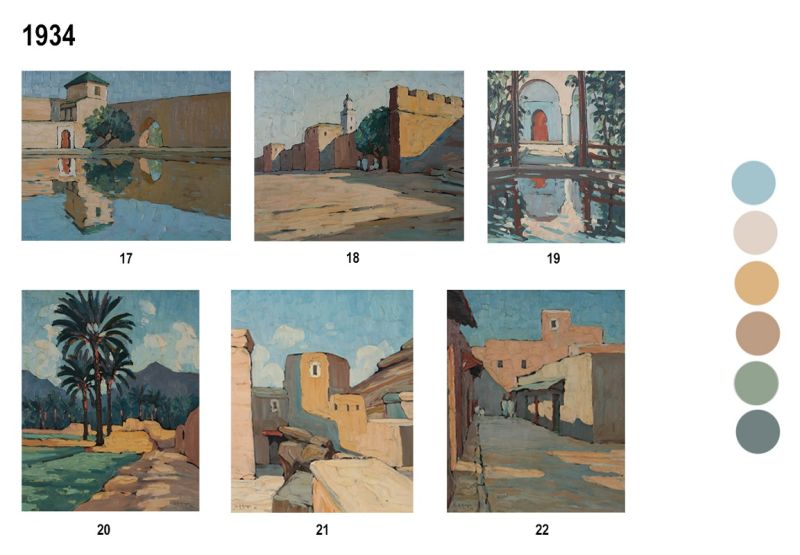

As the research showed, in 1929 Mangin mainly painted pictures of the landscapes and monuments of south-western Syria. He dated only one work of the same subject matter to a year later. He painted pictures of the Syrian cities of Malaula, Kuteife, Damascus and Ad-Dumair as well as the ancient ruined city of Palmyre. Two works from 1929 and another one from the following year focus on the French island of Corsica, specifically the village of Erbalunga and the beach of Miomo. Three years later, Mangin completed most of his French coastal landscapes, including pictures of the Côte d'Azur (Menton, La Turbie) and others of Corsica. His paintings of 1934, on the other hand, deal exclusively with North African landscapes, especially Moroccan cities (Marrakech, Meknes, Freija, Tiznit), gardens and oases.

Mangin's works are not only convincing because of their unique painterly execution, but also contain a special value in terms of contemporary history. Especially his paintings of ancient Syrian and Lebanese and ancient Roman cities and monuments are important contemporary documents. While Ch. A. Mangin captured them pictorially in the early 20th century, they are no longer preserved today, almost 100 years later, as they have been destroyed by the IS war. Through painting, those important cultural monuments are kept alive. These very works will become even more important and valuable in the future because of their subject matter.

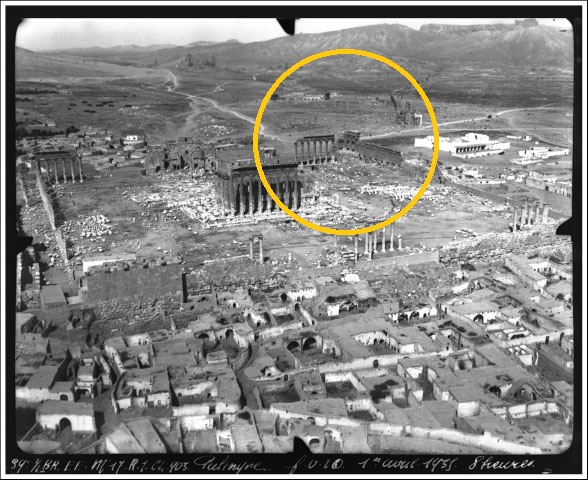

His work "Palmyre. Le village près du Temple du soleil " (Figure 4) from 1929 shows a part of the ancient ruined city of Palmyra. The entirety of the ruined city becomes clear in a photo (Figure 5) from 1935, which was taken only six years after the dating of the oil painting.

The yellow mark in the photo shows the place from where the artist painted and what scenery he depicted there of the ruins with a view of Qalaat Ibn Maan Castle in the background. In the centre of the ancient oasis city, the Temple of Baal can be seen in the photo. In 2015, Palmyra and parts of the Temple of Baal, the Baal Shamin Temple and the Arc de Triomphe were destroyed by IS.

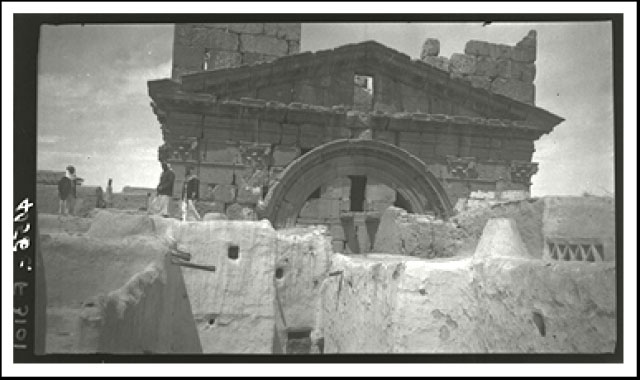

Another work by Ch. A. Mangin depicts an important Roman monument: the Roman Temple ad-Dumair (Temple of Zeus Hypsistos) (Figure 6). The photograph (Figure 7) was created at the same time as the oil painting.

The photo proves that the artist reproduced the buildings realistically, even if he followed an expressive painting style. In both pictures, one can see that the temple had not yet been completely excavated at the time. The uncovering of the temple at ground level did not take place until 50 years later. His oil paintings show a past condition that no longer exists today. They are of significant importance in recording the history or even the complete existence of historical buildings.

His work "Baalbek Syrie - temple de Bacchus" (Figure 8) represents another special feature. The painted view of the entrance gate of the temple of Bacchus is a popular motif in art. Almost 100 years earlier, the English painter David Roberts painted the entrance from the same perspective in 1941 (Figure 9).

In direct comparison, it is noticeable that at the upper edge of both pictures a piece of the central closing element seems to have broken off in the course of these two dating years: an important piece of information for the documentary recording of the temple, which is still standing today.

Painting technique

Towards the end of the text, we return to the beginning: to Mangin’s unique painting technique.

Like many artists of his time, Mangin painted in oils. He applied his characteristic oil paints, consisting of a brilliant blue, reddish-brown or sandy hues, thickly and without primer directly onto the support. He mostly painted on plywood panels and less on textiles (canvases). On the one hand, this was probably for economic reasons, as the former are cheaper painting supports. Secondly, the plywood panels were easy to transport. They can be easily stacked on top of each other and are less fragile or resilient, which is an advantage when traveling and painting outdoors.

Another indication that Mangin completed the artworks on site or during his travels is the condition of the paint layer. In some places, the impasto layer of paint has been pressed down. This means that the paint layer must have been in a drying but still unsolid or "soft" state when something weighty was placed on it. The artist probably painted the paintings on location and stacked them on top of each other during transportation before the paint layer was completely dry or "solid". The damage was caused by the artist himself during transportation or handling. It is therefore damage that was caused not much later and by a third party, but shortly after the painting was completed and thus represents a special original feature.

In the period from 1929 to 1934, of a total of 22 works, only three canvas paintings are documented, all of which are dated to the year 1929. These are exclusively Syrian-themed paintings. As noted at the beginning, several different colours can be detected in what initially appears to be a monochrome tone. This is because the artist did not mix the paint completely. When he dipped into the paint, he took the colours adjacent to each other on the colour palette right away and applied them directly to the carrier. Thus, traces of green, yellow and red can be found in the light red tone, shades of yellow in the blue colour, and the colours blue, green and red in the purple (Figure 10).

This technique adds a more intense colourfulness and dynamism to his radiant paintings.

Furthermore, Mangin deliberately used his painting tools to create a very specific surface effect for different areas and thus achieve a contrast in the visual appearance.

He skilfully alternated brush and palette knife, which can be seen in almost all his paintings. The French artist rarely executed a landscape painting with only one brush, and even more rarely with only one palette knife.

If both painting media are used in a work, Mangin usually used the brush for the dark colours, the shadow areas but also the sky. He deliberately used the palette knife for the light areas and for the accents on the surface, or to deliberately create contrasts or structures in an area of the painting, such as the floor. The palette knife creates a smooth surface and is perfectly suited for depicting flat areas, but also for setting bright light accents in the landscape. The hanging brush creates more structure in the plane and achieves greater detail, which is why it was often used for uneven grounds, for trees, for waves, for figures and so on by Mangin (Figure 12).

Besides his special painting technique, his radiant oil colours are of interest.

His colouring changed over time. Depending on the setting, his colour palette seemed to change in the period from 1929 to 1934.

There are three works that do not carry a date (Figure 13). The Syrian and Lebanese paintings on the left (no. 1) and right (no. 3) were probably painted in 1929 or 1930. The painting in the middle (no. 2) depicts an alley in the coastal town of Menton in southern France and can therefore, like another painting of the same town, probably be dated to 1932. The colour palette of these three paintings plays an important role in understanding his subject-conditioned choice of colours. The tones of these vary from a dull pale yellow, light white, light blue to a dark orange-red.

Mangin's works from 1929 are thematically mixed with Syrian as well as French landscapes. Surprisingly, red tones dominate the colour palette (Figure 14). They vary from a bright red, to a dull red-orange with a violet undertone, to a dark rusty red-brown. White and the same blue, here slightly more intense, play only supporting roles. Moreover, the white is dominant only in the Syrian works (Nos. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9).

In the following year, works Nos. 11 and 12 (Figure 15) complement the two subjects just mentioned. They are listed mainly for the sake of completeness and complete the knowledge gained about the colour palette of 1929, even if it appears to be lighter here.

The year 1932 marks the French year. It was the year of his visit to Corsica and his trip to the Côte d'Azur. The painter's palette here (Figure 16) lives from the varying shades of red, the soft pastel yellow and pastel blue. The deep reddish brown, the violet undertone and the pink appear as in 1929, only this time they seem calmer.

The North African pictures seem to be lighter in colour overall (Figure 17). The dark tones only appear in the leaves of the trees or the bushes. The sandy tones, the velvety blue and the dull green dominate his colour palette.

It is noticeable that the colours are warmer for the North African theme. They match the fertile palm gardens, the Moroccan gardens, the surrounding sandy desert landscapes and the Mediterranean coast of North Africa. Compared to the French subjects painted at the same time, the Syrian pictures have a higher proportion of white, as the Syrian buildings are made of light-coloured stone, among other things. The surrounding landscape contrasts with this in a reddish brown. In the colouring of the southern French coastal pictures, on the other hand, there is much more blue (of the Mediterranean and the high sky). The landscape is also rendered in a rusty red tone. The red is more intense here compared to the Syrian paintings.

Conclusion

The striking, deliberate, expressive, recognisable and identifiable, unique painting style of the artist Ch. A. Mangin captivates the viewer. It is the paintings that speak for the artist, tell something about him. The previous scientific explanations brought the viewer closer to the artist and encouraged him to take a good look at the picturesque landscapes of the French artist in order to share the beauty discovered in them.

The blog aimed at acknowledging a (still) unexplored painter and the identification of an artist through his works themselves. It was meant to encourage readers to take a closer look at the more inconspicuous works of art from time to time, in order to discover something special in them as well. They are often good for a surprise.

Anyone who would like to receive the article in its entirety, i.e. with additional information on the signature and differentiation to the better known French sculptor and painter of realism, Charles-August Mengin (1853 - 1933), as well as a tabular analytical overview of the works studied, can request this in writing an email to hello@art24.world.