Dying and Death - Conciliatory Words and Images from Philosophy and Art History

Philosophy about Death

Plato and the Afterlife as Liberation of the Soul

In Plato's ‘Phaedo’, one of his most famous dialogues, death is understood as the separation of body and soul. For Plato, the body is a kind of prison for the soul, and death frees the soul so that it can transition into a purely spiritual existence. For Plato, the transition to the afterlife is not tragic, but a return of the soul to the realm of ideas, where it has access to true knowledge. In Plato's conception, death marks the transition to a higher, divine existence.

Immanuel Kant and The Incomprehensible Nature of The Afterlife

In his Critique of Pure Reason (1781), Kant also addressed the question of what lies beyond life. While he does not engage in metaphysical speculation about the afterlife, Kant views death as a limit of human understanding. For him, dying is not a transition that humans can fully comprehend, but an experience that lies beyond human knowledge. At the same time, according to Kant, moral action is characterised by the belief in an immortal soul - the idea of the afterlife serves as a moral compass.

Martin Heidegger and The ‘Being to Death’

In his masterpiece ‘Being and Time’ (1927), Martin Heidegger takes up the topic and describes death as the ultimate possibility of being that defines human life. He uses the term ‘being towards death’ to emphasise the fact that human existence is always in the face of death. Death is not seen as an isolated event, but as a fundamental condition for understanding existence: By recognising the terminality of his life, human beings become aware of the significance of their own actions and decisions.

Jean-Paul Sartre and The Nothingness

In contrast to Plato and as a continuation of Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre sees death in a purely materialistic sense. In his main work ‘Being and Nothingness’ (1943), he describes death as the ‘nothingness’ that awaits human kind. For Sartre, there is no afterlife, no continuation of the soul. Death ends man's existence completely. This idea of death is linked to the existentialist idea of the absurd: Life has no higher meaning and humans must define themselves without relying on a future existence in the afterlife.

Albert Camus and the absurdity of life

In his work ‘The Myth of Sisyphus’ (1942), Albert Camus, also a representative of existentialism, sees death as part of the ‘absurd’ state of life. Life is meaningless and full of contradictions, and death ultimately leads to the realisation of this absurdity. Nevertheless, Camus calls on us to accept this state and find the courage to lead an authentic life in the face of death.

Works of Art about Dying and the Transition to the Afterlife

Art has often depicted dying as a moment of transition to another form of existence, whether through religious, symbolic or metaphorical imagery. Here are some significant examples that deal with dying and the transition to the afterlife:

William Blake - The Soul Hovering over the Body and Reluctantly Parting with Life (1805)

This drawing is a powerful depiction of the moment of death. It shows the moment when the soul leaves the body, which Blake depicts as a deeply symbolic and spiritual process. Blake, who was influenced by Christian and mystical ideas, saw death as the liberation of the soul from the body. In this work, he illustrates dying as a process that is associated with emotions such as hesitation and fear, but ultimately leads to redemption. The depiction of the floating soul expresses this tension - holding on to life, but also recognising the necessity of the transition to the afterlife. However, it challenges people emotionally and metaphysically.

Arnold Böcklin - The Isle of the Dead (1880)

Arnold Böcklin's ‘The Isle of the Dead’ (Kunstmuseum Basel, 1st version, 1880) is one of the most famous works to thematise the transition to the afterlife. The painting shows a small, rocky island. A boat with a cloaked figure and a ferryman approaches the island. The work is an allegorical depiction of the transition of the soul into the realm of the dead. The sombre, silent atmosphere of the painting makes death appear as a mysterious, perhaps peaceful transition, while the ferryman recalls the ancient image of Charon carrying souls across the river Styx to the realm of the dead.

The 2nd version is in New York at the Metropolitan Museums of Art.

The 3rd version is in Berlin.

The 4th version was destroyed in the 2nd World War.

The 5th version is in the Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig.

Gustav Klimt - Death and Life (1910/1915)

Klimt's painting ‘Death and Life’ is another allegorical depiction of death as an unavoidable part of human existence. Death, depicted as a skeleton with a colourful robe, is juxtaposed with life, which is depicted in all its vitality and beauty. Here, Klimt conceives of dying and death not only as the end of life, but as a constant companion that emphasises the fragility and preciousness of life. In this symbolic depiction, death is understood as part of a natural cycle that makes the transition to the afterlife inevitable.

Frida Kahlo - Death as a Constant Companion

Frida Kahlo was very close to death due to her own health problems and her proximity to Mexican culture, in which death is seen as a natural part of life. In her self-portraits, she often shows symbols of death, such as in ‘Henry Ford Hospital’, in which she thematises the loss of a child and the fragility of her body. Kahlo once said: ‘I have survived two major accidents in my life. The first was the bus accident, the second was Diego [her husband].’ Her humour in the face of the tragic events in her life shows how much death was present in her art and her thinking.

Edvard Munch - Death and Loneliness

Edvard Munch's relationship to death is strongly characterised by his personal biography. The early death of his mother and sister left him with deep emotional wounds. In his work ‘Death in the Sickroom’, he shows how death destroys families and leaves behind deep loneliness. Munch himself described his work as a ‘reflection on human tragedy’ and said: ‘Illness, madness and death were the angels that accompanied my life.’ For Munch, death was not an abstract concept, but a painful reality that haunted him personally time and again.

Georgia O'Keeffe - Aesthetics of Death

While many artists depict death as a tragic event, Georgia O'Keeffe sees the beauty and permanence in death in her paintings of animal bones and desert landscapes. In works such as ‘Cow's Skull: Red, White, and Blue’ (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), death is not depicted as something sinister, but as something that has its own quiet beauty in nature. O'Keeffe reflected on how death was omnipresent in the desert, but at the same time could also have a calming effect in its permanence.

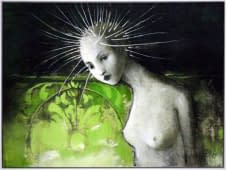

Thomas Haensgen and His Works ‘Duality’

Thomas Haensgen takes an approach to the themes of dying and death in his current works. It is remarkable that these were created while Haensgen himself was in a coma four times due to several brain infections, each time a zero line was temporarily recorded by EEG, but he miraculously survived each of these four times. One or rather four very extraordinary experiences richer.

In the art historical tradition, there are few examples of artists who take death as their subject in such a personal and direct way as Haensgen does in ‘Duality’. While death in art is often staged as an allegory, symbol or stylistic antithesis to life, in Haensgen's works it remains a lived, lived-through experience. In a way, this is reminiscent of Goya's ‘black paintings’ (Prado, Madrid), which convey a deep sense of finitude in their gloom and existential pessimism - but unlike Goya, Haensgen refuses to resort to the abysmal or the threatening. He chooses a completely different path: the light, clarity and structure in his works do not suggest finality, but rather a transition, a passage.

This idea of transition - both aesthetically and thematically - links Thomas Haensgen with artists who made transformation the leitmotif of their work. Marcel Duchamp, for example, whose work ‘Étant donnés’ (Philadelphia Museum of Art) ventured a similar glimpse into another, almost inaccessible reality, showed that the afterlife can also function as a formal enigma in art. But while Duchamp depicted the afterlife as a mysterious and closed space in which the secret remains hidden, Haensgen opens up the view. His works are not puzzles to be deciphered, but open windows that show a world that is not visible to the viewer.

This transparency in dealing with the hereafter is perhaps the most radical gesture in Haensgen's current works. At a time when modern art often favours deconstruction and ironic distance, ‘Duality’ comes across with astonishing sincerity. Haensgen does not play with the usual mechanisms of art theory or postmodernism, which propagate the end of ‘grand narratives’. Instead, he goes in the opposite direction - he tells the greatest story of all, that of life and death, without claiming to be able to fully understand or explain it. This attitude, which seems almost humble in its simplicity, lends his works a deeper dimension.

This idea of merging and cancelling opposites can also be felt in the structure of Haensgen's series. The title ‘Duality’ refers to the apparent paradox of life and death, but the works themselves suggest that this duality is an illusion. Instead, Haensgen sees life and death as part of a larger, indivisible whole. This idea is reminiscent of the philosophy of Taoism, in which the ‘yin and yang’ principle states that seemingly opposing forces are interconnected and interdependent. Haensgen's works illustrate this principle visually: life and death permeate each other in a constant flow, and the transition from one state to the other is not a break, but a natural, flowing movement.

In the reception of ‘Duality’, it is therefore not only the artist's personal background that is important, but also the philosophical and spiritual level that he weaves into his works. His photographs challenge the viewer to pause and reconsider their own relationship with death - not as a final end, but as part of a larger, infinite cycle. The visual language Haensgen chooses for this is as clear as it is subtle: through the use of light and shadow, by blurring the boundaries between reality and abstraction, he succeeds in creating an atmosphere that is simultaneously calming and mysterious.

Conclusion: Dying and The Afterlife in Art and Philosophy

Dying and the transition to the afterlife are central themes in art and philosophy that have been reflected upon for thousands of years. While philosophers such as Plato, Kant and Sartre developed different approaches to the meaning of death and existence after death, artists have often created symbolic, religious or metaphysical representations of this transition. Dying is seen as both the end and the beginning of a new existence - be it in the sense of a spiritual rebirth, a metaphysical separation or a final disappearance. Art and philosophy thus offer us diverse perspectives on the greatest mystery of human existence: death.