The forest. Of its depiction as wilderness, mystery, and place of idyll to the resource.

Note: Technical terms are shown in italics the first time they are mentioned and explained in a glossary at the end of the text.

The meaning of the forest reflected in art

“[...] And I write that I am very happy and that I would be glad if you were here, because there are things in the woods that you could lie in the moss for years thinking about.” (Franz Kafka, postcard to Max Brod from Spitzberg in the Bohemian Forest, 18 September 1908, translated from German into English.)

Franz Kafka wrote these lines to his friend Max Brod in 1908. The forest inspired the author and brought him happiness and a feeling of closeness to nature. But the forest also allows other emotions and associations. It is mystical, fabulous, dangerous, wild, powerful, glorified, lonely, idyllic, natural, an obstacle, animal kingdom, place of retreat and longing, as well as threatened by exploitation and destruction. The list is long.

Depending on the historical context, the forest as a natural space had positive or negative connotations, for its significance and function changed as frequently in society as the colours of the trees in autumn. The ways of depicting it in art are therefore always an expression of this relationship between humankind and nature at a particular point in time. It becomes clear that the forest continues to shape people today through its almost unavoidable presence.

If we imagine Kafka's European forest, he probably saw many large trees, adorned with dense leaves and conifers, but also meandering forest paths that allowed him to immerse himself deeper and deeper into the woods. But what he felt at that moment remains his secret.

Today, the forest reminds us of tranquillity and idyll. This was not always the case. For a long time, the forest was something impassable for humans and therefore something wild, far away from civilisation, which also gave bandits the opportunity to attack travellers. For these reasons, it was often perceived as a place of danger. For hermits in the late early Middle Ages, on the other hand, the forest offered the solitude they sought, mainly for religious reasons. For travellers, it was not only a place of danger but also an obstacle, as roads through European forests did not exist until well into the 18th century. It was only afterwards that the wilderness became less and less dangerous thanks to the network of paths which brought it closer to the cultivated area. However, it was still not without danger, as it was the habitat of wild animals such as wolves and bears. The idea of the forest as an idyllic and tranquil place of power and recreation is new and has been pushed forward above all since industrialisation, when cities and industry intervened more and more in the natural world to help themselves to its resources of wood and land. In art, the forest was initially depicted accordingly, unnoticed and reserved. This was reflected in the fact that it was always painted as an accessory and never as an independent motif. Vegetative elements were usually depicted crudely and schematically in fresco and book painting, as ornamentation or in architecture, for example on capitals. These were usually only isolated plants that served a symbolic or decorative function in the overall work, or functioned as a reference for an entire landscape area. However, there were also impressive exceptions.

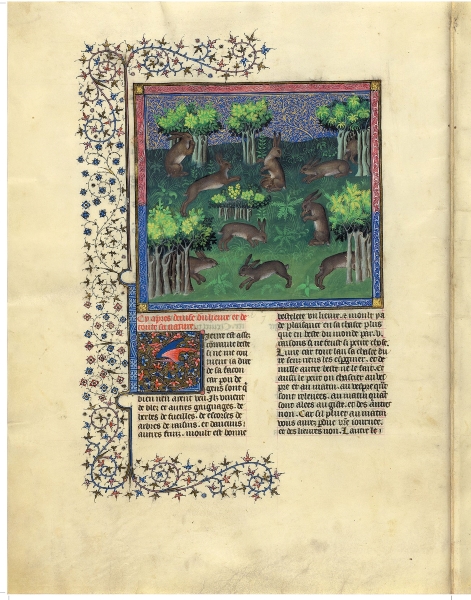

In book illumination, «The Book of the Hunt» (fr. «Livre de la chasse») is noteworthy. This late medieval work was illustrated with miniatures in 1407.

In it, the surroundings of the animals shown were depicted in great detail and in a differentiated manner, from mountain forests to deciduous forests to coniferous forests. Here too, however, the plants had mainly an ornamental function without any depth. The forest was only ever subordinated to the context of the narrative as staffage. Thus, the depictions did not convey any contents or ideas of a specific, closed natural space.

In the Italian Gothic and the early Renaissance, the forest was depicted, for example as a juxtaposition of individual trees, with a little more space, but it still remained a peripheral phenomenon.

It was not until the 18th century and with landscape painting in Western Europe that the forest was slowly discovered as a subject, stimulated by secularisation. Eastern European art stuck to the iconographic guidelines for a little longer. East Asian cultural areas, whose art spread to Europe with the new trading connections, also expressed a view of nature that differed from Western painting, such as Chinese literary painting or Japanese and Chinese woodcuts, influencing European art.

Slow transformation of its meaning

After the forest had long represented the untouched environment and accordingly appeared schematic, stylised and loaded with symbolism, it slowly underwent a change of meaning and was depicted more and more realistically. This late recognition also resulted from the fact that it was simply easier to depict the wide, open landscape than a closed, complex and dense world of trees. As a place of danger, the forest was probably only reluctantly depicted with greater precision. Its purely symbolic-metaphorical meaning was also more significant for a long time: in Christian motifs, it served to suggest paradise or the wilderness, which only had to be reproduced in characteristically abbreviated form. The depicted forest often also promoted meditative contemplation (meditatio) to support the comprehension of the central story. It was thus only meant to refer, to underline the central motif as a backdrop and to serve as a contrast.

Around 1500, the perception of the forest changed. Interest in nature grew at this time, especially under the influence of Dutch painting and through the writing of Germania Generalis by Conrad Celtis, in which the forest was no longer described as a wilderness and a place of danger, but as a place of freedom and a landscape that structured the German Empire. People who lived in the forest, so-called «wild people», were described as honest and simple. They served as role models because they were not influenced by worldly objects. The seclusion in the woods was now perceived as noble, while people in civilisation were considered corrupt. The forest thus became a glorified place.

At this time, the clearing of forest areas as raw material for mining and metallurgy also increased, which meant that the common property of the forest and the use of the wood in it had to be regulated more and more. In painting, however, the forest continued to be used for clair-obscur depictions of religious or mythological motifs - groups of saints are illuminated by light, while the forest brings darkness with it, so that the eye automatically turns back to the main motif. These religious/mythological and allegorical depictions were still being painted until the 17th century, for example as altarpieces and devotional pictures, or in history painting. The staging of light in these scenes often represented shelter and dwelling, which is further emphasised by the dark contrast created by the forest.

However, the depiction of the forest became increasingly detached from this type of devotional painting. This is shown, for example, by Albrecht Dürer's graphic works or the works of the so-called Danube School, like the painting 'Danube Landscape with Wörth Castle' by Albrecht Altdorfer, which can probably be regarded as the first pure landscape painting, since it contains no human staffage.

The forest now appeared to be independent and thus worthy of art, even though small human figures were still frequently integrated into the landscape.

What is remarkable in this turn is the individualisation of the forest. It broke away from its connotations as wilderness, the uninhabited or as a reference to paradise. It took on a new meaning as an alternative to the city and everyday life, which manifested itself in the 17th century in the genre painting of the «forest still life», a genre of its own that originated in Holland. However, the forest was still depicted only suggestively in the form of forest details. City scenes surrounded by flat nature were shown on the horizon, or the sea and its expanse, due to Holland's nature, which was only scarcely characterised by forest.

The forest is loaded with new, but also dangerous feelings

As can already be seen from the blog post «Flowers in Painting», nature was revalued due to the secularisation of Europe. The church and monarchs lost influence through the Age of Enlightenment and the revolutions, which also led to a redefinition of the commissioning parties and, in turn, to new pictorial content being requested. Nevertheless, this was far from being a fully representative, independent natural space, as picture titles such as «Landscape with Forest» or «Woody Landscape» reveal. Landscapes were still not depicted directly and on location as a whole. Rather, individual aspects were recomposed as sketches and notes in the studio. But the difference was that situational conditions and personal experience were incorporated into the work. These experiences were to be reproduced accurately and logically, as in Caspar David Friedrich's well-known Romantic work «The Chasseur in the forest» from 1814.

The diverse «epoch» of Romanticism dissolved compositional and perspectival orders, for the overall form became freer and transported emotional, subjective elements. Nature now inspired. However, it was still subject to the label of depicting the ideal landscape.

The Romantic period was characterised by a strong sense of nature. Nature was considered a place of refuge for the soul. The forest was given more space, but at the same time it was also charged with sensations and symbolism, as for example in fairy tales. In literature, the forest was elevated to a place of desire and escape. This led to a romanticisation of the forest, which now aroused feelings of nationality and promoted a sense of identity. With reference back to antiquity and the Middle Ages, the forest was seen as the origin of the «Germans». This also influenced later National Socialist art. The aim was a realistic representation in the classicist manner, accompanied by an idyllic character that was intended to emphasise the sense of home. These images, oriented towards the «German forest», became a collective identification. This was still the case, for example, with Anselm Kiefer in the Informel art of the 1950s, who used them to try to address the National Socialist past and to investigate the origins of this symbolic language.

The forest thus only moved to centre stage as a pictorial motif late in the 19th century. Particularly with the rise of open-air painting, nature became increasingly important as a stand-alone object worthy of art and as a space of experience. William Turner, Alexandre Calame, his student Friedrich R. Zimmermann and the artists who formed a group in Barbizon, to name just one place, should be mentioned here (Learn more about the «Artists' colonies»).

Through this new way of painting, artists discovered the forest for themselves. Forest paths made it accessible, which meant that striking places such as certain caves, groups of oaks, ravines or clearings could be painted. The atmosphere that prevailed in the depths of the forest was thus also in focus. This is particularly evident in the titles of paintings, which were now called «Forest Edge» or «Clearing in the Forest». Also, the human being and his dwellings disappeared from the depictions. The result was a contrast to the industrialised, mechanised city, a return to «primordiality». The landscape depictions also stood in the field of tension between the progress of painting and one's own well-being, which was stimulated by the retreat into nature. Immersion in the forest - similar to Romanticism - promoted its mystery.

The new, ephemeral form of painting, caused by rapidly changing light conditions, reached its peak in Impressionism. The liberation of painting generated new ideas about the nature of things, resulting in a wide range of avant-garde movements. The forest broke away from an analytical/naturalistic rendering. Max Ernst or Ernst Ludwig Kirchner come to mind. The focus was now on form, colour, movement, possibilities of view or impressions. If we look back at the images of National Socialism, they seem anachronistic and backward-looking in comparison.

New forms of expression in modernity

After this break in art, the detachment from painting and form continued from the 1960s onwards. Abstract art and minimalism emerged. Now, references to the forest were usually only made with the help of language or symbolic materials, for example as conceptual art. Objects linked to industry and the use of wood only refer to the forest. Notable examples include Christo's «Wrapped Tree» (1968), Robert Smithson's «Dead Tree» (1969), Giuseppe Penone's «Ripetere il bosco» (engl. «Repeating the forest»), but also photographs and films such as Nancy Holt's work «Pine Barrens: Trees» (1975). What is striking in these works are the deforested trees without leaves, reduced branches that stand or lie only as «dead» matter in a room or in the sparse landscape. Humans take what they need. In modern art, the forest is represented as a resource and a capital-generating commodity, based on an alienation from the forest: products made from the raw material wood are no longer associated with their origin.

Beverley Buchanan's small house sculptures, which she called «shacks» from the 1980s onwards, also function as references. In addition to the raw material wood from which the simple American Southern dwellings are made, they also draw attention to real, socio-political conditions. At the same time, they refer to living in wood in general: human beings used this material for living more than 10,000 years ago. Joseph Beuys, founding member of the Green Party in Germany, also dealt with the forms of living, in contrast to Buchanans, through action art. The publicity inherent in this, as well as in the «political», was used by Beuys to emphasise the blurred boundaries between art and politics and thus to express his concerns for the environment. This was also the case in his work «7’000 Eichen- Stadtverwaldung statt Stadtverwaltung» at documenta 7 in Kassel in 1982, which involved many different specialists, administrative offices and authorities, as was typical of Beuys' «extended concept of art». The performance involved planting 7’000 trees throughout Kassel over several years with the help of volunteers. His aim was to draw attention to the capitalist changes and to give space to nature again. The cityscape should be made greener again.

Modern art history is thus also about the political relationship between humankind and nature, which is obviously thematised. Actionism and art also went hand in hand in Bruno Manser's work. The Swiss ethnologist lived in the jungle in Borneo with the Penan, who suffered from the massive deforestation of the rainforest and were driven out of their habitat. Among other things, Manser used his action art to raise awareness of the timber trade and the timber industry. In 1986, for example, he knitted jumpers for the Federal Councillors in front of the Swiss Federal Parliament to draw attention to his cause and symbolically warm their hearts to the situation. Today, historical photographs still bear witness to his political actions.

The photorealistic works of the artist Franz Gertsch, on the other hand, confront us directly with the forest and its essence, but also with its value for us, through its appearance. In the work «Sommer (Detail)» from 2009, the forest is staged as a detail. In the process, the artist projects a part of the work as a photograph onto the canvas, which he in turn translates into painting. In this way, he allows the viewer to dive into the depths of the forest, both mentally and physically, through the size and realistic nature of the work. Through contemplation, one' s perception and sense for the forest is sharpened and nature is thus honoured as art.

The forest in the Anthropocene era

Plastic arts and installations with forest motifs initially existed mainly conceptually, as with the land art artist Richard Long or Beverley Buchanan. But in recent art, these art practices are becoming more relevant. The influence of globalisation and urbanisation is a particular issue here, because although the forest is often regional, it is a worldwide issue in the context of global warming.

In 2019, for example, Klaus Littmann placed an entire forest in the middle of the «Wörthersee» football stadium in Klagenfurt! The intervention was entitled «FOR FOREST - The Unbroken Attraction of Nature» and represented a memorial of nature in the Anthropocene. The forest remained in the stadium for 50 days, framing it and thus elevating it to an emotional experience, similar to what the football game is for many people. Through the framing and the foreign location, the forest clearly moved into our consciousness - and thus also our familiarity and connection with it. The trees were exposed to the autumn weather and changed accordingly. The influence of the climate on the forest and its importance for our future is abruptly brought to mind, but also the beauty of this event and the fear of loss associated with it.