Through Impressionism and Cubism to Camouflage

The Impressionists and the Discovery of Camouflage

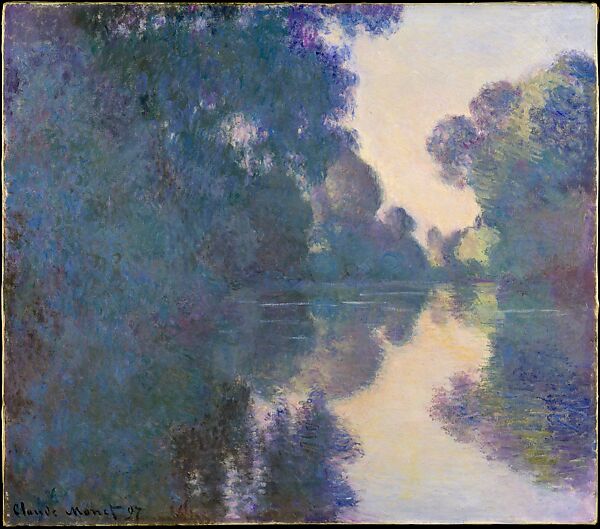

The Impressionists, who emerged in the late 19th century, revolutionised the art world with their emphasis on light and colour. Artists such as Claude Monet, Edgar Degas and Pierre-Auguste Renoir sought to capture the fleeting impressions of the moment. Their technique of using quick brushstrokes and bright colours reflected a new way of perception.

During the First World War, the link between Impressionism and camouflage became clear. One notable case is the French artist Lucien-Victor Guirand de Scévola, who served as an officer in the French army. He recognised that the Impressionist painting technique, with its dissolution of contours and colours, was ideally suited to camouflaging soldiers and equipment. He said: ‘Impressionism in painting is the direct forerunner of camouflage in battle’ (‘L`impressionnisme en peinture est le précurseur du camouflage sur le champ de bataille’). He was convinced that the impressionist technique of depicting light and shadow, which promoted the blending of colours and shapes, was an ideal basis for camouflage. This gave rise to the idea of military camouflage, in which the boundaries between objects and their surroundings were blurred in order to conceal them from the enemy's eyes.

Cubism and the Further Development of Camouflage

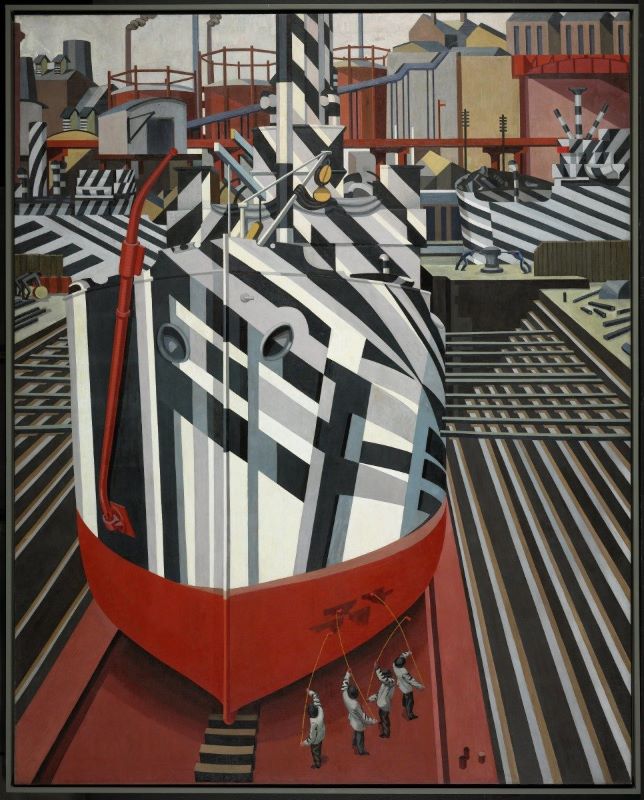

Cubism, developed at the beginning of the 20th century by artists such as Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, brought another dimension to the art of camouflage. This movement focussed on breaking down objects into geometric shapes and depicting them from multiple perspectives simultaneously. Cubist works are often characterised by their fragmentation and the use of hard lines and shapes.

Cubism also found a military application during the First World War. The Cubist technique of fragmentation and the overlapping of forms was used to develop complex camouflage patterns that broke up the contours of vehicles and buildings. Picasso himself is said to have said that he and Braque were the inventors of camouflage, as their artistic methods provided a perfect basis for military camouflage. In his own words, when he saw a tank in camouflage for the first time during the First World War: ‘It was Cubism that did it.’ (‘C'est nous (the Cubists) qui l'avons fait’).

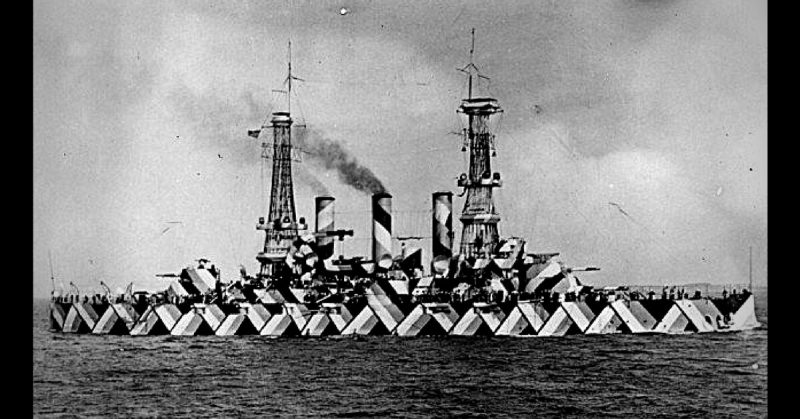

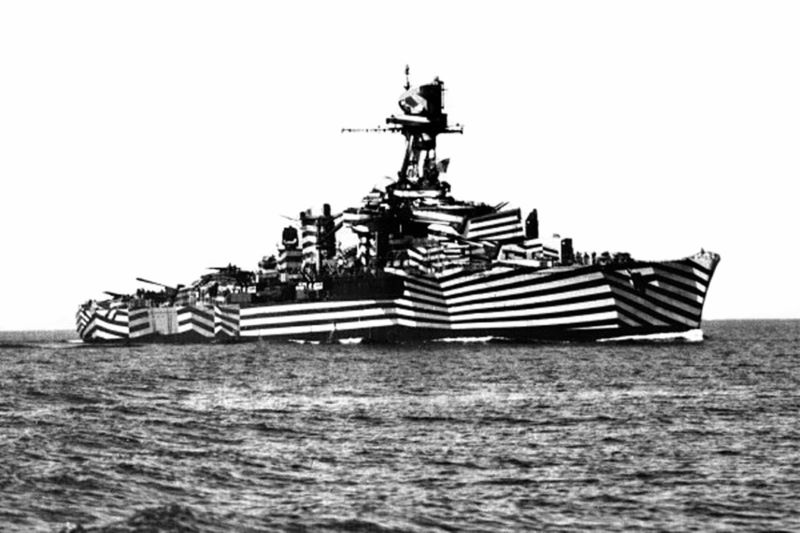

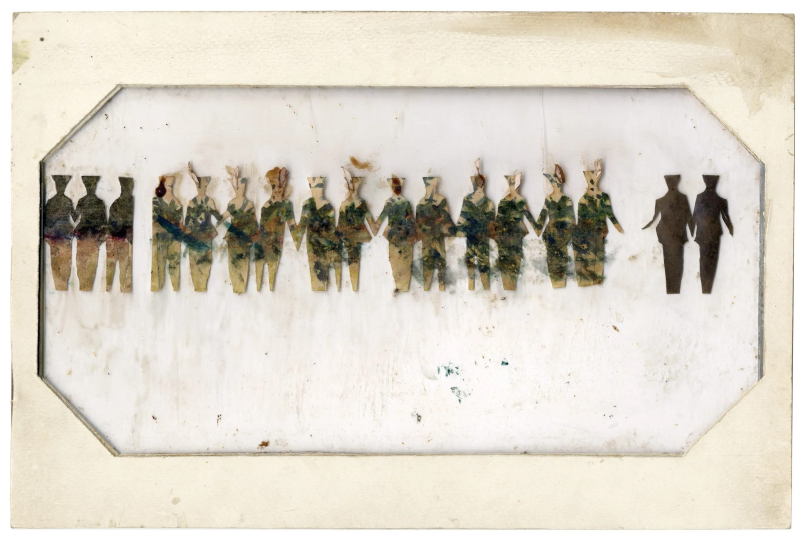

One particularly interesting example is the so-called ‘Dazzle Camouflage’ (stencil camouflage), which was developed by the British artist Norman Wilkinson. This technique utilised high-contrast, geometric patterns to disguise the shape and movement of ships at sea. Dazzle camouflage was a direct application of cubist principles and was widely used during the First World War.

The artist Edward Wadsworth was also a prominent exponent of dazzle camouflage, utilising Cubist principles to camouflage ships. He later transferred these techniques into his art, creating paintings that depicted the high-contrast, geometric patterns of dazzle ships. Wadsworth's works reflect the close connection between art and military practice.

Military camouflage and artistic experimentation

As one of the pioneers of camouflage, Abbott Handerson Thayer emphasized the importance of “disruptive patterns in nature. He argued that many animals, such as the peacock, become invisible in their natural environment by breaking up their silhouettes with irregular patterns. Although his theories were not always taken seriously in his time, they later had a significant influence on the development of military camouflage.

Thayer said in reference to his research: “Nature knows no lack of tricks to hide her treasures.” His studies on camouflage were eventually taken up during the First World War and were incorporated into military practice.

A Funny Anecdote to End With

An interesting incident during the First World War shows the connection between art and camouflage: the artist André Mare, a cubist who served in the French army, was commissioned to develop camouflage patterns for military equipment. When he completed the first camouflaged tank, an officer said: ‘This is a masterpiece of modern art, but how do you use it in war?’ (’ C'est un chef-d'œuvre de l'art moderne, mais comment l'utiliser en temps de guerre? ‘). This anecdote illustrates how the innovative art of the Cubists was put at the service of the war, arousing both admiration and scepticism.

Art and the Military: A Reciprocal Relationship

It is remarkable how the artists of Impressionism and Cubism not only advanced their respective art movements, but also involuntarily contributed to the development of military strategies.

The integration of military techniques into art shows how flexible and adaptable artists can be. At the same time, art influenced the military by showing new ways of camouflage and deception. This reciprocal relationship shows that art and the military can not only learn from each other, but also develop together.

The Impressionists and Cubists each contributed in their own way to the development of camouflage and showed how art can have an impact in unexpected areas of life. Their techniques and innovations live on not only in their artwork, but also in the strategies used by the military to this day.

The fusion of art and the military is a fascinating chapter in history that demonstrates how creative approaches can be applied to the most diverse areas of our lives. The Impressionists and Cubists opened up new perspectives through their artistic experiments and proved that the boundaries between art and reality are often more fluid than one might think.