Rainbow #4 - Renaissance and Early Modern Age

Between the Earthly and the Heavenly

In the cultural movement that began in Italy and that we now call the Renaissance and the Early Modern period, the motif of the rainbow was also given a fascinating and wide-ranging use and interpretation in religious and secular painting. Those decades, which are marked by a revival of forms of ancient art, literature, mythology and philosophy, are rich in lasting discoveries and inventions (for example, technical painting methods such as aerial, coloured and central perspective, the preference for mathematical constructions, the use of geometric figures or the further development of the theory of proportion).

One of the most unconventional and forward-thinking artists, inventors and universal scholars of his time was Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519). This painter-researcher with a thirst for knowledge, who saw himself as an apprentice of nature and its beauties and who recorded his thorough observations and analyses by means of studies, discovered laws of harmony predetermined by nature in the rainbow. On the basis of further observations and scientific findings on harmonic and disharmonic colour gradients, da Vinci created magnificent masterpieces. He is therefore considered to be one of the pioneers of colour theory and colour psychology which were developed later.

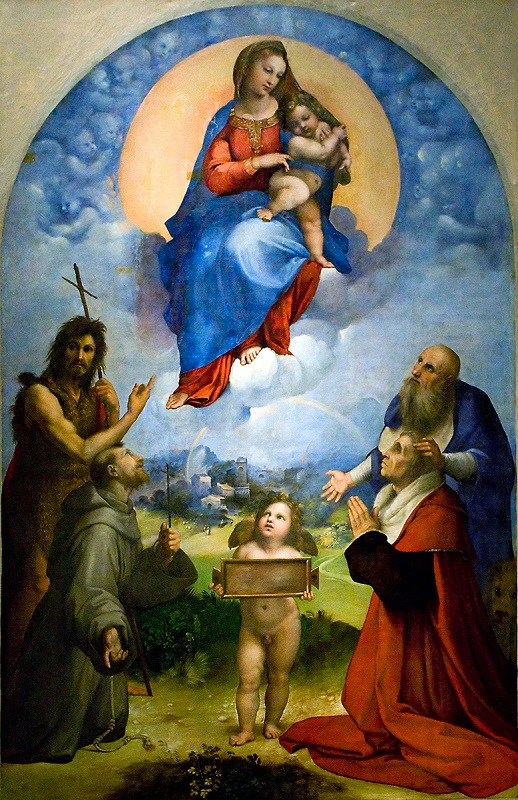

The slightly younger Raphael (da Urbino, 1483-1520), like many other artists of the time, devoted himself entirely to the ideal of beauty. In his view, beauty was only perfect in art as the artist's painted idea, but could not be found in nature (Propyläen Kunstgeschichte, vol. 7, Berlin 1972, p. 153). Raphael's work «Madonna of Foligno» from 1511/12 with a rainbow over the vast landscape with a town and mountains in the background shows this in colour and compositional perfection. The rainbow, placed like a bracket between the earthly and heavenly spheres, is interpreted in this donor painting as a sign of divine mercy, as a symbol of peace, but also as a reference to the end of the world and the approaching judgement.

In those decades, the rainbow could not yet be explained scientifically, even if its painted appearance had outstanding colour qualities. Religious symbolism and references to «heavenly» signs determined its interpretation for the time being. A wonderful example of this is an uncoloured woodcut in Martin Luther's Bible of 1545 on Genesis chapter 9: here the rainbow is a sign of «the covenant between God and man» at the end of the great flood of water and is to be seen as a «divine peace treaty».

Between Worldly Melancholy and a Triumphant Sign of Peace

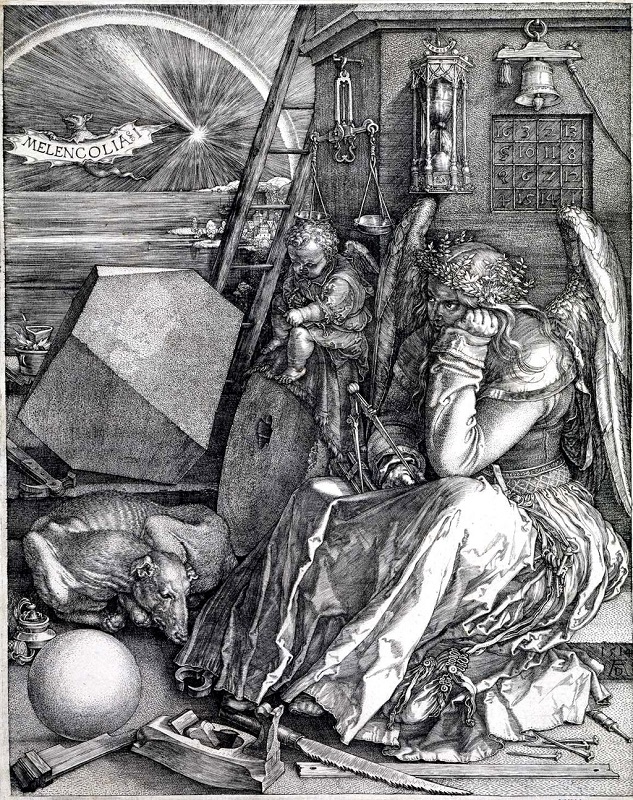

In 1514, the German artist Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) created one of three master engravings in Nuremberg: «Melencolia I».

This copperplate engraving, with its many puzzles that have not been clearly solved to this day, is based on a highly complex symbolism with profound allusions and interpretations around a seated figure with angel wings resting his head in front of a building, accompanied by a dog and surrounded by seemingly randomly scattered objects. In the picture's background, the rainbow spans a radiant comet and the calm sea with a coastal town. The interpretations range from an allegory of Melancholy, specifically «artist's melancholy», which points to a not always existing creativity accompanied by «mental tension», to the interpretation of a turning point in time: the ending of the Middle Ages (symbol hourglass) gives way to the heralded new epoch of the upwardly striving Renaissance (symbols bell, ladder), which Dürer got to know on his travels in Italy. The old or familiar (melancholy) as well as the unfamiliar or new (the symbol light) are spanned by the rainbow as a sign of blessing. Did Dürer, who himself wrote scientific works, want to indicate with the geometric objects and tools in the picture the future scientific tools that would also be available to him as an artist? Despite all the riddles and questions, it remains exciting to see how the rainbow remains connected to the divine sign of blessing in a secular work.

The rainbow in the copperplate engraving of 1564 «Pax - Peace Creates Wealth» («The Cycle of Human Existence, 8») from a cycle by Cornelis Cort (1533-1578) after the preliminary drawing by Maarten van Heemskerck (1498-1574) sets a triumphant sign of peace.

The depiction refers to the annual procession (on the occasion of the «Circumcision of Christ») on 1 July 1561 in Antwerp, which addresses the «cycle of human existence». The personification of Peace sitting in the triumphal chariot, pulled by Concord and Benefit, guided by Cupid and accompanied by Justice, Diligence and Truth illustrates a saying that has been depicted several times since the 16th century: «Peace brings trade, trade brings wealth, wealth brings arrogance, arrogance brings conflict, conflict brings war, war brings poverty, poverty brings humility, humility brings peace». Only when peace reigns again does the country blossom into new prosperity - and this under a rainbow as the triumph of peace.

The Rainbow on the Way to Scientific Exploration

The step towards scientific research of the rainbow had not yet been taken. However, there were isolated artists such as Adam Elsheimer (1578-1610) who incorporated their observations of nature, constellations and natural light sources (of the sun and moon) sketched outdoors into mythological-genre-like and religious scenes or stylised, heroic landscape depictions. Despite their traditional subject matter, his works took on a «near-natural, realistic aura», as can be seen in the atmospheric night painting with full moon «Flight into Egypt» from 1609.

The «Thank Offering of Noah» once attributed to him with a double rainbow (!) as a sign of reconciliation has in the meantime been denied to Elsheimer by researchers... what a pity...

The oldest description of the rainbow and its circular position, which is still valid today, was penned by the natural scientist, mathematician and philosopher René Descartes (1596-1650), who is considered the founder of so-called modern rationalism. However, his explanations for the origin of the rainbow colours proved to be useless. However, he did indicate the path to explore the mysteries and enchantments of a natural phenomenon with the mind, which later led to physical studies and colour theories. You can learn more about this in Part 5 of the Rainbow Series.

Glossary:

Colour theory: The science of colours and the knowledge of their use. It is based on colour systems or colour orders that explain how colours relate to each other in harmony or in contrast, or how they affect people.

Donor painting: A commissioned Christian work shows the client or donor in the context of a religious scene and invites the viewer to pray.

Engraving: In this intaglio printing process, the motif is «dug» (engraved) into a copper plate with the help of a graving tool. The resulting deepened lines absorb the ink and release it onto the paper during the subsequent printing through the roller press.

Allegory: Things that are abstract or unreal are illustrated in the visual arts, for example Cupid stands for love.

Rationalism (Latin ratio): According to this, the acquisition or justification of knowledge is based primarily or exclusively on reason-related thinking. Other knowledge, for example emotional or empirical experiences as well as religious traditions, are not taken into account.

Further Literature:

Panofsky, Erwin. (1975, dt. Ausgabe). Ikonographie und Ikonologie. Eine Einführung in die Kunst der Renaissance, in: Sinn und Deutung in der bildenden Kunst. Köln: DuMont, S. 51ff.

Dickens, Emma. (2006). Leonardo da Vinci. Das da Vinci Universum – Die Notizbücher des Leonardo. Berlin: Ullstein Verlag

Kaulbach, Hans-Martin. (2013). Friedensbilder in Europa 1450-1815. Kunst der Diplomatie - Diplomatie der Kunst; [... erscheint zum Abschluss des Forschungsprojekts »Übersetzungsleistungen von Diplomatie und Medien im vormodernen Friedensprozess. Europa 1450 - 1789«], Berlin / München, S. 110-111, Nr. 52.

Regenbögen für eine bessere Welt. (1977). Trilogie 3. Stuttgart: Württembergischer Kunstverein.