Self-portraits In Art - What They Reveal About Us

When Did The Fascination For The “Selfie” Begin?

In the self-portrait, the artist appears as the creator and simultaneously makes himself/herself the subject. There is a merging of author and subject, whereby the existence of the individual, including their specific individuality, is placed at the centre. Self-portraits were increasingly produced by artists from the early modern period onwards, which is why the motif was long restricted to this era in art history and attributed to it. In the Renaissance, an increased interest in the appearance of personalities can indeed be recognised. But the first self-portraits probably already existed in antiquity. However, the intention of self-portraits seemed to be different from antiquity to the Middle Ages.

Traces of Self-Portraits in Antiquity

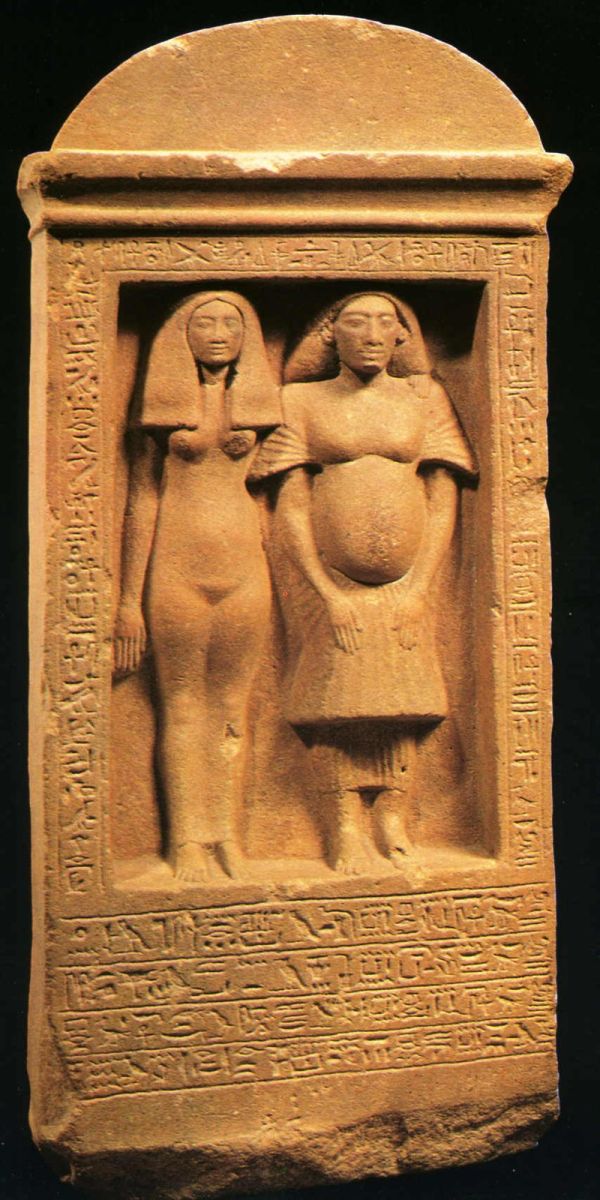

In antiquity, the focus was rarely on the artist's own person, but rather on deities, rulers and mythological figures. In contrast to today, the profession of an artist was considered a craft back then, which is why only a few names are known to us and most of them have remained anonymous. The name was therefore of secondary importance. Accordingly, works from antiquity were only seldom signed. However, some individuals have been passed down, mostly through written sources, while the works have often not survived in their entirety. But on some ancient Greek vases or on paintings and sculptures from Ancient Egypt, we discover artists at work. For example, a well-known early self-portrait is that of the chief sculptor Bak, who worked for the pharaoh Akhenaten (1,365 BC). Plutarch (c. 45-125 AD) also mentioned that the sculptor Phidias (died 430 BC) applied his likeness to the Parthenon in Athens as part of the ‘Battle of the Amazons’ and was arrested for it. We therefore know little about the motivation behind the self-portrait. Society's attitude towards the self-portrait was apparently rather negative. Phidias' crime was therefore probably twofold: the Parthenon was not a place for human depictions, and a sculptor should not take credit for a purely divine work.

In Roman antiquity, portraits of the makers can probably be found in mosaic scenes, demonstrating the craftsmen's skills. However, in this interwoven form, they are not so easy to recognise as their own depiction. This also applies to the motivation behind them. The only name of an ancient mosaicist that we know is that of Sosos (2nd half of the 3rd century or 1st half of the 2nd century BC), who is mentioned in a source by Pliny. A well-known work by the artist shows the motif of the unswept ground in Pergamon. An imitator of Sosos signed his work of an unswept floor with the name ‘Heraklitos’, which is now in the Vatican Museum. We therefore have a deliberately placed signature here.

Getting Closer to God: The Self-Portrait In The Middle Ages

Even in medieval Europe, the actual self-portrait was hardly widespread. In the High Middle Ages, however, the creators emerged more self-confidently in so-called artist inscriptions, albeit in the guise of faith. Above all, however, their merits and artistic mastery were supposed to bring salvation and create a special closeness to God. Nevertheless, self-portraits are regularly found in artistic works. An early example is a medallion in the gold altar of Sant'Ambrogio in Milan, which was created by Vvolvinus around 840-845 AD. In this medallion, the goldsmith appears on an equal footing with the donor, but unlike Bishop Angilbertus, he presents his empty hands. This is because his merit is the craftsmanship, i in other words the altar itself. With this, the craftsmen hoped to enter the realm of the blessed. Vvolvinus' talent as an artist and his creative power enable him to be close to God and should bring him salvation.

Self-portraits in illuminated manuscripts were also widespread. These manuscripts were only accessible to a few people, as they were produced and used in and for the sacred world. The scribes or decorative artists sometimes depicted themselves in miniatures or initials in order to identify themselves as the creators of these elements or the script. This is therefore an indication that it is a self-portrait during the activity.

In some cases, the scribe and illuminator were one and the same person. These were mainly monks in monastic scriptoria, before the production of manuscripts became “industrialized” and manuscripts were also produced outside of monasteries in bourgeois scribes' workshops. Some of these presumed self-portraits cannot be assigned a name and are therefore anonymous. Others, however, are clearly identified by a text nearby, which states or suggests that the image depicts the artist himself or herself. A famous example of such a portrait is that of Matthew Paris, a monk who lived in St. Alban's Monastery near London in the 13th century (1200-1259).

A well-known self-portrait in Europe, which is not found between pages of parchment but as a fresco painting on a wall, is that of Johannes Aquila from the 14th century (1392). He depicted himself praying in the parish church of St. Martin in Martjanci, Slovenia, where the signature Johannes Aquila de Rakersburga oriundus identifies him as “Johannes Aquila from Rakersburg”. At the same time, he also provides information about his education in perfect Latin. Thus, in addition to his face, we know the name of the fresco artist from the late Middle Ages, which is a rarity.

Where Is The Beginning Of a Self-Portrait?

But what can actually be considered a self-portrait? Some Roman citizens of antiquity commissioned portraits of themselves, for instance. This could be in the form of mosaics or reliefs for their villas or on public buildings, as well as tomb reliefs that were commissioned during their lifetime and show the individual in an idealized form. They were therefore able to express their wishes, which were then realized by a craftsman. This meant that they had an influence on their appearance in the depiction, even if they were not the executing hands. The same applies to depictions of rulers, especially on coins. Could they therefore also be considered self-portraits, even though they did not have complete authorship over their image?

The self-portrait was long to be found in the context of a larger oeuvre, which was predominantly dedicated to religious or stately art. In the course of the professionalization of the occupation, in which the artist as a person increasingly came into focus and helped determine the market value, their self-image also changed. More and more self-portraits were created in which artists staged and tested themselves. From today's perspective, self-portraits are representations of the artist and locate their mastery in the context of history.

Development in The Renaissance

But sometimes it was also pure necessity. The famous Renaissance artist Artemisia Gentileschi, for example, probably painted herself partly because models were expensive and it was forbidden to paint nude models for a time. Her own body and her own portrait were the only alternative. However, there are also self-portraits by her that clearly focus on her self-confidence as an artist. For example, her allegory as a painting, in which she depicts herself with wild hair and the allegory is thus no longer to be understood as purely such, but also goes beyond it. The self-portrait can therefore be used in different ways and does not necessarily have to serve an idealization of the self.

One of the most captivating, well-known and relevant self-portraits is that of Albrecht Dürer. It shows the artist life-size in frontal view, directly addressing the viewer. This kind of frontal view had previously only been used for Jesus Christ or certain rulers. Dürer thus boldly and confidently joins the ranks of the nobility as an artist and elevates the status of his profession as an artist, which had previously been seen primarily as a craft. He demonstratively shows us his hand, which realizes his ideas and creates works of art. He also wears a fur coat, another sign of nobility that was previously only reserved for this class.

In portraits, there is always a connection to ideas of life and death. We see this particularly impressively in so-called mummy portraits from the Egyptian-Hellenistic period. Although these are not self-portraits, they suggest to us how the practice of recording one's own self is connected to the fleeting nature of life and was firmly embedded in a cultural practice. These portraits were made from the 1st century to around the middle of the 3rd century AD and usually show the person in a frontal view as a bust or head portrait. Attached to the mummies, they represented the deceased in the afterlife. This technique allowed facial features to be preserved for eternity. Dürer's self-portrait, as well as many other self-portraits, are based on this desire to capture and remember oneself forever. This is therefore one function of the self-portrait for the artist. However, it also shows the talent and possibilities of art to reproduce true-to-life images, as well as to bring the past closer through art.

The Mirror as a Guarantee of Reality?

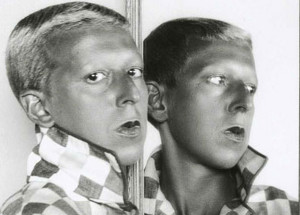

Artists could only capture themselves so precisely with the help of one instrument: The mirror. Parmigianino's self-portrait in a convex mirror (1523/24) shows the young artist in the object in which he sees himself and through which he can reproduce himself. In the form of the trompe l'oeil, the self-portrait comes very close to reality and the conditions under which it was produced. Parmigianino thus demonstrates his skills. On the one hand, the mirror serves artists as an “[...] instrument of knowledge and self-knowledge [...]” (Pfisterer and von Rosen, p. 50), but on the other hand it is also untrue, because it reverses the sides, enlarges or reduces, distorts at the same time and thus also deforms the truth. The mirror is therefore ambiguous and so are the possibilities of self-presentation. It invites self-observation and self-questioning, but can also reveal the artificiality of the image and thus open up a playing field.

Manifold Possibilities of the Self-Portrait

In painting, many other examples can be observed that show and identify the artists at work and thus remain visible for posterity forever, while at the same time bringing the unsolvable mysteries of the person depicted closer. But there are also examples in other media, such as sculpture. The sandstone self-portrait by Adam Kraft (around 1500), which can be found in the St. Lorenzen Choir in Nuremberg, or the bust of the cathedral builder Peter Parler, also made of sandstone and on display in St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague, are examples of this. In these cases, the objects are linked to the architecture and are intended to be placed in this context. However, there are also works in which the artist presents himself as a sculpture independently of the architecture. The slightly larger-than-life sculpture by Bertel Thorvaldsen, for example, stands there self-confident and broad-legged, showing us his working tools while at the same time working on a female sculpture and demonstrating his work to us.

The exact reproduction of a likeness is still a popular method today. But can a person also immortalize themselves without their exact image? Dürer was not alone in painting objects that were closely linked to his body and that can be seen as another form of self-staging. Just as Dürer painted his cushion, Vincent Van Gogh painted his shoes (1886). The worn shoes are often seen as a hidden self-portrait of the artist. Such substitutes, detached from the direct body, were widespread in art around 1800.

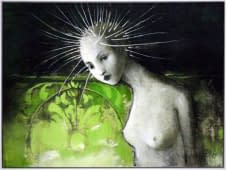

When photography emerged, a new, precise and fast method of staging became possible without the need for a mirror and prolonged observation. Claude Cahun and Lee Miller, for example, posed in front of the camera and explored ideas of self-love, independent of the male gaze. Meret Oppenheim showed herself as an X-ray image in 1964. Completely exposed, we see her inner self and experience a new reality. But at the same time, the new view also conceals. In addition to Meret Oppenheim, other artists also played with new technology. Jeff Wall (Double Self-Portrait, 1979), for example, doubles his own person in the photograph, while Gerhard Richter obscures the sharp photograph again and thus appears as a projection surface (Hofkirche, Dresden, 2000). The artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres, who made so-called “word portraits”, worked in a completely different way. This included one of himself entitled “Untitled” from 1989.

Similar to Van Gogh or Dürer, he does not show the outward appearance of a person, but goes one step further. In a non-figurative pictorial language, he opens up a new form of image. In this installation, the writing becomes the subject of the picture, revealing information about the person. Could this be even more accurate than an image of the person? The artist thus stimulates a person's imagination and at the same time reflects the words back onto the person looking at them.

The Self-Portrait: Mirror of the Self and the Outside World

The medium also determines which questions and answers a self-portrait reveals about a person. The question of the self is therefore difficult to answer even for the creators of the images. The human being seems too complex. Artists therefore have the power to create images and realities, but at the same time their works are also exposed to the view from the outside and thus to external evaluation. Self-portraits create a human connection and allow us to explore not only the self of the person depicted, but also our own self. This seems to be the beauty and fascination of the self-portrait.