Rainbow #7 - In the Age of Reason and Enlightenment

Use your Mind...

It was philosophers and scientists who laid the foundations for the Enlightenment with their writings on tolerance, freedom, progress and rational thinking and attacked both religious and ecclesiastical views. For example, Immanuel Kant's statement «Have the courage to use your own reason» (1784). This sentence is considered one of the most significant maxims of that time, which not only gave philosophy a new direction. With the increasing emancipation of the bourgeoisie, which demanded its own rights and questioned the supremacy of the aristocracy, the field of art and culture also received an exciting publicity through contemporary exhibitions, the emergence of art criticism, theory, reception and the founding of academies, especially in London and Paris as the most important art market centres in Europe. And when the glorious heydays of aristocratic culture began to fade after the first half of the 18th century, Enlightenment theories with moralising, educational as well as rational programmes could no longer be stopped. The perception of the beautiful and the natural, of a simple and clear representation in art that should awaken sensations in the viewer, became the subject of numerous theoretical treatises on art (for example by Johann Georg Sulzer). And the study of light and the spectral colours of the rainbow, as the art24 blog «The Faces of Colour Theory» already addressed, were also analysed more closely in those decades.

...and Paint!

So far so good on the theoretical side. But how did all these Enlightenment tendencies and theories affect the visual arts How did they affect artists who used the motif of the rainbow, especially as it had been used for many centuries as a symbol and was often not reproduced in a visually correct way? The influence of Isaac Newton's colour wheel, the discoveries of his successors that derived from it and the invention of further colour pigments should not be underestimated for the «revolution of colours» and their «merging» in the 18th century. One of the artists who was inspired by Newton's colour wheel was the brilliant and successful artist Angelika Kauffmann (1741-1807). During her stay of more than a decade in London, she created her painting «Colour» (fig. 1). This colourful commissioned work is one of a total of four ceiling paintings for the headquarters of the Royal Academy at Somerset House, later Burlington House. Already the grisaille sketch (fig. 2) preparing for the painting shows the beautiful fusion of symbolism, iconography and science, interspersed with her own artistic ideas.

Fig. 1: Angelika Kauffmann, Colouring, 1778 to 1780, transverse oval ceiling painting, 130 x 149.5 cm, Royal Academy of Arts, Somerset House, London. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Fig. 2: Angelika Kauffmann, Colour, grisaille sketch oil on paper, 1778-80, 22.4 x 28 cm, Prints & Drawings Study Room, Level C, Case MB2A, Shelf DR80, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Photo: Victoria and Albert Museum.

A young artist, in the middle of a rocky landscape, is extracting paint from a rainbow with her brush. In her other hand she holds a palette with a dab of white paint (symbolising white light). While this scene represents the genre of painting and colour as one of the elements of art, the small chameleon at her feet represents the variety of colours in nature. Complementing the rest of the ceiling paintings with further elements of art («invention», «composition» and «design»), Angelika Kauffmann adopted the views of Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792). This painter, passionately devoted to colour in theory and practice, was the first president of the then still young Royal Academy in London, of which Angelika Kauffmann was also a founding member. The contents of his lectures on painting and colour were therefore sufficiently familiar to her. Soon Kauffmann's painting was spread as an engraving by Francesco Bartolozzi (1727-1815) - her fame as «...perhaps the most cultivated woman in Europe» (Gottfried Herder to his wife Caroline 1789), who knew how to illustrate theories with great skill, was further consolidated.

The portrait of «Archibald Montgomerie» from 1783/84 shows that Sir Joshua Reynolds was not only able to theorise about colour and light as valued subjects. Reynolds' portraits, which mostly depicted spectacular, optically precisely observed celestial atmospheres, were highly sought-after. Archibald Montgomerie, 11th Earl of Eglinton, who appears like a saint under a circle of light (halo), impressively reflects Reynolds' exact observations of nature, also with regard to colour gradients.

Fig. 3: Sir Joshua Reynolds, Archibald Montgomerie, 11th Earl of Eglinton, 1783-1784, oil on canvas, 76.2 x 63.5 cm, Royal Collection of the British Royal Family.

Benjamin West (1738-1820), the second president of the Royal Academy, also knew how to use brilliant language to encourage his students to use colours correctly, for example in 1897 in his lectures on «Principles of Colouring in Painting» or «The Warm and Cold Colours» (p. 115 ff.), which were published in 1820 in «The Life, Studies, and Works of Benjamin West». That in this context the rainbow was also mentioned as a shining example for the correct use of colours may hardly seem surprising.

The English painter Joseph Wright of Derby (1734-1797) also had a strong interest in natural science, and his works seem to glow from within with dramatically staged light effects. One of these masterpieces is «A Philosopher Giving that Lecture on an Orrery, in which a Lamp is put in the Place of the Sun from» 1766. Since light was considered the symbol of the Age of Enlightenment par excellence and played a significant role in many respects, Wright reveals himself as its great representative, depicting and at the same time appreciating the acquisition of rational thought and knowledge.

Fig. 4: Joseph Wright of Derby, A Philosopher Gives a Lecture on the Planetarium, 1764-1766, oil on canvas, 147.3 x 202.2 cm, Derby Museum and Art Gallery, Derby, England.

Wright's Landscape with Rainbow was painted in 1794, with a probably fictitious location. A year earlier, the artist had told his friend and patron John Leigh Philip, «I am trying my hand at a rainbow effect». It was a new subject for him, presumably inspired by earlier landscape depictions with rainbows by Peter Paul Rubens, for example, which Wright, however, supplemented with his own studies of nature and out of personal interest in weather phenomena - entirely in the Kantian sense of «making use of one's own intellect».

Fig. 5: Joseph Wright of Derby, Landscape with a Rainbow, 1794, oil on canvas, 81.2 x 106.7 cm, Derby Museum and Art Gallery, Derby, England.

Spiritual, Mystical Colour Gradients

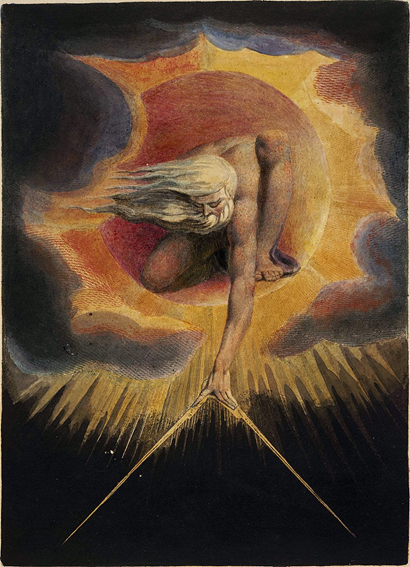

However, the art of the 18th century was characterised by far more than just individual, Enlightenment subjects, especially since it is hardly possible to speak of a pure Enlightenment art, but rather of enlightening art. The pictorial motifs of distant universes, threatening apocalypses, erotic scenes and human anatomy were too complex, and the artists were too imaginative in their implementation of thoughts and visions. One of these visionaries was William Blake (1757-1827), who, however, found little recognition as an artist, poet, nature mystic and inventor of the relief etching. In the same year as Wright's rainbow painting was painted, Blake wrote his poem Europe a Prophecy with numerous illustrations, from which the following example is taken:

Fig. 6: William Blake, Europe a Prophecy, 1794, relief and white line etching with colour print and hand colouring, 36 x 25.7 cm, The British Museum, England, Photo: British Museum.

A figure resembling God the Father in an expressive red-orange iridescent sun formation with a lower halo of rays, surrounded by grey-blue clouds, is kneeling, his back bent, his arm outstretched and holding an oversized compass in his hand, ready to take measurements. What this «circumscribing» entails and what it refers to lies literally in the dark for us viewers, perhaps also for the «architect» himself. This luminous colour gradient in Blake's prophecy underlines the artistic views in many ways: on the one hand, Blake sees himself as an artist connected to the divine, who wanted to lead people to a spiritual renewal; and on the other hand, he created his own mythological creatures (for example, Ork as the spirit of energy), which are to be understood as symbols for his views on historical and political grievances of his time. Blake used the circle here as a sign of the Freemasons, who were seen as supporting «architects» of the revolutions in France and America. Politics, spirituality, revolution, history, wisdom - everything interpenetrates, and should always be circled anew.

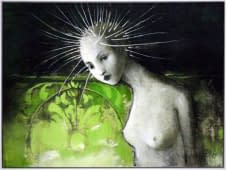

_800pix.jpg)

Fig. 7: William Blake, Beatrice Speaks to Dante, 1824, 37 x 53 cm, ink and watercolour on paper, Tate Gallery.

In William Blake's imagination, the guidance of Dante (1265-1321) by his great love Beatrice through the heavens could not be more colourful and seductive to the eyes and senses - with fine iridescent colour nuances, somewhat like rainbow colours, the artist illustrated this scene at the end of Dante's «Divine Comedy» of 1321, thus already catapulting himself into the next artistic epoch - the age of Romanticism. Once again, Blake, together with other artists, demonstrated that enlightenment is the realisation of reaching new ideas and spheres by using one's own thinking and intellect, in order to be able to leave even science and research far behind. The next article in this blog series will reveal how art took on the rainbow after 1800.

Further reading:

Steffen, Martus. (2015). Aufklärung. Das deutsche 18. Jahrhundert. Ein Epochenbild. Berlin: Rowohlt.

Saltzwedel, Johannes (Hg.). (2017). Die Aufklärung. Das Drama der Vernunft vom 18. Jahrhundert bis heute. DVA Spiegel Verlag.

Kay Kankowski (2012). Die Entstehung bürgerlicher Öffentlichkeit im 18. Jahrhundert, München, GRIN Verlag, https://www.grin.com/document/192628.

Further links: