Rainbow #8 - From Romanticism to Art Nouveau

Romanticism: An Epoch Full of Emotions and Moods

The aftermath of the French Revolution with its social changes and the Napoleonic Wars (until 1815) still kept the world in suspense, when the age of Romanticism increasingly grew as a reaction to scientific explanations, rational thinking and industrial progress. The embattled concept and feeling for freedom was joined by the multi-layered «I» of humankind with individual feelings, thoughts, moods, affects, personal experiences, as well as the glorification of the Middle Ages and the admiration of natural beauty, to which the arts paid great attention. The works of Romanticism made use of a wide range of emotional, passionate, fantastic, overwhelming, but also frightening and unpredictable feelings, which were supposed to evoke empathy when reading a poem or looking at a landscape painting. Successful were those creative, inspired artists who knew how to combine the visual with the emotional.

From Good Fortune Bringer to a Natural Phenomenon

«Gray and gloomy and more and more gloomy / The weather comes on, / Lightning and thunder are over, / You are revived by a rainbow / Granting joyful signs / The earth never tires of; / For many thousands of years / The arch of the sky speaks: Peace / (...) / Wild storms, waves of war / Have rested over grove and roof; / Yet eternally and universally / The colourful arch is here.»

This is how Johann Wolfgang von Goethe described his experience of nature in the summer of 1814 (during wartime) on the journey to Wiesbaden in the poem «Rainbow over the hills of a graceful landscape» . As a writer with a great interest in colour theories, he often reworked his beloved motif of the rainbow (see art24-rainbow blog #5). On that trip, however, he saw in the «colourful bow» a sign of happiness and hope - and it can hardly be a coincidence that in Goethe's house in Weimar there was a painting on the ceiling depicting the goddess Iris and a rainbow.

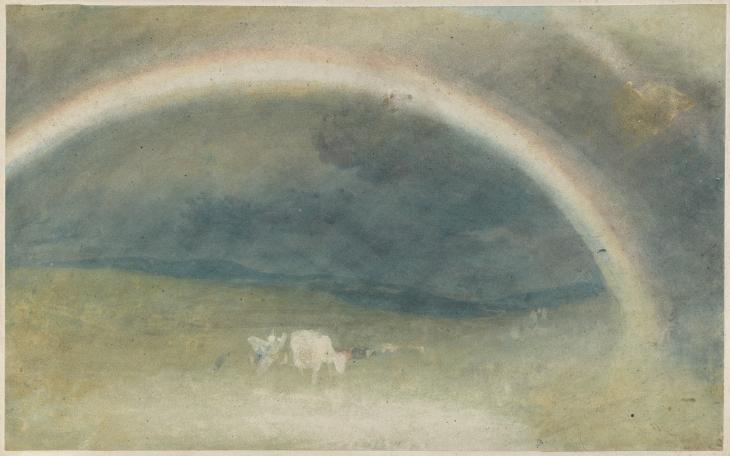

William Turner's (1775-1851) watercolour study «Rainbow with Cows» from 1815 presents itself like the visualized image of Goethe's rainbow poem:

Fig. 1: Joseph Mallord William Turner, A Rainbow, with Cattle, c. 1815, watercolour on paper, 25.6 x 41.5 cm, Prints and Drawings Cabinet, Tate Britain (Turner bequest CXCVII G).

Against heavy dark storm clouds in the depths of the hilly landscape, Turner's rainbow dominates lightly and loosely set above a wide meadow plain with grazing cows. A flash of blue sky at the top of the painting announces better weather. Another watercolour with a rainbow shows masterfully and almost puristically how Turner realized weather phenomena with light, air and atmosphere in a fascinating way:

Fig. 2: Joseph Mallord William Turner, A Rainbow, c. 1820, watercolour on paper, 35.3 x 48.8 cm, Prints and Drawings Cabinet, Tate Britain (Turner Bequest CXCVI R).

He rightly advanced to become the most important and influential landscape painter of his time. As a «painter of light», he gave the motif of the rainbow the status of a natural phenomenon. Now the rainbow, meticulously observed outdoors, is sufficient solely for itself, without being symbolically charged.

In the colourful rainbow paintings by John Constable (1776-1837), another outstanding landscape painter who rivaled Turner in terms of composition, personal, spectacular observations of nature are combined with symbolic content:

Fig. 3: John Constable, Landscape and Double Rainbow, 28.7.1812, Oil on canvas, 33.7 x 38.4 cm, Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

From a Symbol of Hope to a Sign of Peace

Despite a close examination of events in the sky, Constable also saw in the rainbow motif a symbol of hope. For example, in the «Double Rainbow» painting, which was created during a visit to his birthplace in Suffolk, and in the melancholy watercolour «Stonehenge», which was created during a painful and sad time for him: in addition to the departure of his two sons, he suffered under the loss of his wife Maria and his best friend. Especially in his late work he regularly depicted rainbows, which as the «most beautiful phenomenon of light» deeply impressed the painter.

Fig. 4: John Constable, Stonehenge, 1835, watercolour on paper, 37.7 x 59.1 cm, Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

A rather unusual, irritating rainbow motif is found in the work of Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840), whose painting was considered the epitome of Romantic art even during his lifetime.

Fig. 5: Caspar David Friedrich, Mountain Landscape with Rainbow, 1809/10, oil on canvas, 69 x 102 cm, Museum Folkwang, Essen.

Under the gloomy, cloudy sky with a pale arch, a figure in the foreground, illuminated by sunlight, leans against a rock and looks into the vast mountainous landscape. Lonely, small and lost, the human figure appears in the face of natural forces in a higher, thus divine sphere and in the threatening as well as sublime world - a topos that was often used by Romantic painters. With the white bow as a sign of the covenant between God and man, Friedrich, for all his Romantic sublimity, still stands in the tradition of religious pictorial works of previous centuries (cf. art24-Rainbow-Blog 4).

Colour Accents and Painting Outdoors

Fig. 6: Jean-François Millet, Le Printemps, between 1868 and 1873, oil on canvas, 86 x 111 cm, Musée d`Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais, Paris.

Despite socially critical pictorial content, the realistic painter Jean-François Millet (1814-1875) also devoted himself to scenic beauty. In the work «Spring» he depicts the dawn of a new season in a lyrical-poetic manner: while cut branches still recall winter, blossoming orchards and planted fields reflect the coming fertile months. Nature dominates. Not the human being who cultivates and builds on it. Barely recognizable standing under a tree in the background, humankind becomes part of the landscape. Millet took fresh colours , which - quickly set - fix the atmospheric situation with different light effects as a snapshot. The fact that a rainbow accentuates the harmonious composition of the picture in terms of colour gives away Millet's closeness to a style that was called Impressionism a little later.

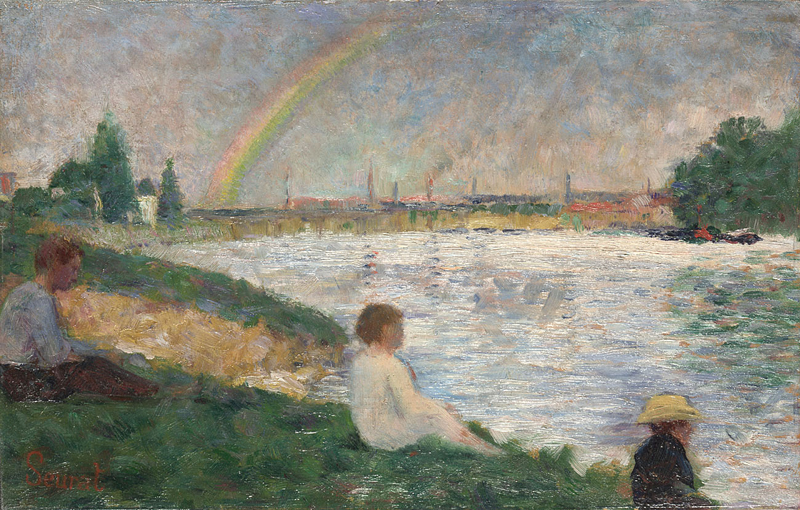

With Georges Seurat (1859-1891) we are already entering the post-impressionist phase of pointillism. Millions of juxtaposed dots of colour create shimmering, vibrating pictorial surfaces. Seurat made dozens of preliminary studies for the large painting Bathers at Asnières (1884). The one shown here is the only one with a rainbow painted over the sky after the paint had dried. Because of the special, atmospherically iridescent sky, the artist could indeed have seen a real rainbow and captured it on the canvas outside in the open air.

Fig. 7: Georges Seurat, The Rainbow: Study for «Bathers at Asnières», 1883, oil on wood, 15.5 x 24.5 cm, The National Gallery, London.

The Rainbow at the End of the 19th Century

For them, too, nature in combination with historical or mythological references was of great importance: for the representatives of Symbolism (from around 1880) and the Pre-Raphaelite style, which emerged in England as early as around 1850. Painted meticulously, rich in detail and with the finest gradations of colour, the works of those phases reflect an overabundance of profound, symbolic allusions that dive into mysterious, divined spheres. An example is the early 20th century Symbolist work Daughters of the Mists by Evelyn De Morgan (1850-1919). Enveloped in diaphanous robes, four airy beings present themselves among clouds, in rays of light-filled, iridescent surroundings and a delicately captured, but inverted rainbow that underscores the ethereal situation. De Morgan was probably referring to Hans Christian Andersen's tale of the Little Mermaid, who is encouraged by the daughters of the air to do good deeds for 300 years so that she will eventually become immortal. Which is illustrated in the picture by the star.

Fig. 8: Evelyn De Morgan, Daughters of the Mist, 1910, oil on canvas, 119.4 x 101 cm, Watts Gallery, De Morgan Collection, Cannon Hall, Barnsley, England.

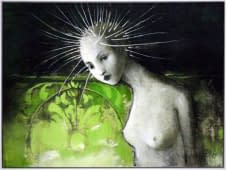

Fig. 9: Alfons Mucha, Painting (from the cycle The Four Arts), 1898, various techniques on paper, Mucha Museum / Mucha Trust 2017, Prague.

The Czech Art Nouveau artist Alfons Mucha (1860-1939) created pictures of high aesthetics combined with floral ornamentation and homage to female beauty. In the cycle «The Four Arts" from 1898, one of his most ambitious projects, he pays homage to painting with balanced ornamentation in the personification of a graceful, stylised female figure, surrounded by decorative patterns that appear in the background in rainbows and rainbow-coloured circles against a cloud-covered sky. In the most beautiful Art Nouveau ornamentation and without the use of attributes, Mucha takes up a tradition-steeped theme that served as a model for countless reproductions and as an expression of his joie de vivre.

With this artist, we leave a century that was varied in styles and, from this point of view, interpretatively rich in motifs of the rainbow. The next blog will be devoted to the 20th century in the form of an overview.

Further reading:

Bockemühl, Michael. (2018). Kunst Sehen - Die Malerei des 19. Jahrhunderts. Bd. 1. Frankfurt/M.: Info 3 Verlag

Ciseri, Ilaria. (2004). Die Kunst der Romantik: Beginn einer neuen Empfindsamkeit. Stuttgart: Belser AG

Görner, Rüdiger. (2021). Romantik. Ein europäisches Ereignis. Ditzingen: Reclam Verlag

Zimmermann, F. Michael. (2020). Die Kunst des 19. Jahrhunderts. Realismus, Impressionismus, Symbolismus. München: C.H.Beck Wissen

Further links:

Belle Époque – die Kunst des späten 19.Jh. – WELTKUNST

Kunst des 19. Jahrhunderts - Landesmuseum Oldenburg (landesmuseum-ol.de)