Rainbow #9 - The 20th Century: Until 1960

Dazzling Through the «-isms» Styles

Seen through the lens of painting, the 20th century began with a bang: in Dresden, Paris and Munich, groups of artists such as «Die Brücke», «Les Fauves» and «Der Blaue Reiter» were founded within a decade. Their expressive, spontaneous painting is characterised by dominant colour combinations that arise from an individual emotional state. In this period of Expressionism, rainbows are probably recognisable as such. However, they are less a depiction of reality than an expression of personal emotions that support the painterly composition of the picture, for example in the work of Wassily Kandinsky, the co-founder of «Der Blaue Reiter»:

Fig. 1: Wassily Kandinsky, Murnau - Landscape with Rainbow, 1909, oil on cardboard, 33 cm x 42.8 cm x 0.4 cm, Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus and Kunstbau Munich, Gabriele Münter Foundation 1957.

Franz Marc, the second founder of «Der Blaue Reiter», even goes one step further. In his work «Der Turm der blauen Pferde» (eng. The Tower of Blue Horses) from 1913, which is considered lost since the end of the Second World War in 1945, various elements are revealed: on the one hand, the artist's idea that nature or animal and cosmos form a unity, symbolised by the rainbow as a bridge between earth and sky. On the one hand, the artist's idea that nature and the cosmos form a unity, symbolised by the rainbow as a bridge between earth and sky; on the other, the incorporation of expressionist, cubist and abstract characteristics that Marc had experienced through the French painter Robert Delaunay (1885-1941), whom he had met the previous year, and his abstract compositions characterised by light and colour. These were obviously reflected in the «Tower of Blue Horses». The rainbow is thus transferred to the dimension of an intellectual-spiritual level, which therefore no longer has to follow a reality-based depiction.

Fig. 2: Franz Marc, The Tower of Blue Horses, 1913, oil on canvas, 200 x 130 cm, considered lost since the end of the Second World War in 1945.

The Rainbow Beyond the Visible World

The fact that artists consciously disregarded outdated academic rules that no longer did justice to modern life in order to find contemporary answers in all genres of art was also due to scientific inventions and new findings that emerged around the turn of the millennium, such as X-rays, microscopes and film, Einstein's theory of relativity or Sigmund Freud's ideas in the field of psychoanalysis. Paul Klee (1879-1940) and his experimental creativity repeatedly combined the results of research and science with his own observations of nature. The extraordinary artist was driven by the desire to «create something new» and to reproduce «the building blocks of life» in new forms of painterly expression. After initially being inspired by the cubist works of Braque or Picasso or by Robert Delaunay's circular, brightly coloured abstractions, which had a decisive influence on Klee's perception of representational dissolving, he found his own pictorial language. His watercolour «mit dem Regenbogen» (eng. With the Rainbow), inspired by Delaunay, has a rainbow spanning an abstract, symmetrically constructed landscape of angular bands of colour in the upper centre of the picture - directly below it is a dark building with a tower, reminiscent of a church, which ends in a blue circle. Man-made strips of fields and constructed water channels versus the cosmos, the celestial sphere - symbolised by the blue disc and the rainbow - catapult Klee's work, created in the middle of the First World War, into the contemporary Avant-garde with its timeless visual language, which has left all realistic reproduction behind.

Fig. 3: Paul Klee, with the rainbow, 1917, 56, watercolour on primer on paper on cardboard, 17.4 x 20.8 cm, privately owned, Switzerland, on deposit at the Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern.

While initially still attached to Impressionism and Expressionism, the Romanian artist Arthur Segal (1875-1944) also developed his own abstract formal language from 1914 onwards, in which all objects, figures and elements are treated equally within painted grids that (can) extend to the frame. The door is open for completely abstract works.

_800pix.jpg)

Fig. 4: Arthur Segal, Rainbow (prismatic), 1924, oil on canvas with painted wooden frame, 105.4 × 85.7 cm, Art Institute Chicago, gift of Richard Roth.

In the «prismatic rainbow», this principle makes a spectacular appearance: within the rectangular grid, a rainbow divided into many coloured stripes is given a new geometric order and thus a new pictorial meaning. The focus does not lie on the rainbow as a motif, but on the rhythmic structuring of the picture surface with the help of fanned-out rainbow colours that have to follow a pattern. However, the fact that Segal discovered and used Goethe's theory of colour for himself is hardly recognizable.

The Rainbow as a Bearer of Hope?

Max Beckmann's (1884-1950) «Eisenbahnlandschaft mit Regenbogen» (eng. Railway Landscape with Rainbow) from 1942 gives the motif of the rainbow a further connotation. The artist, who had left Nazi Germany for good in July 1937 and emigrated to the Netherlands, gave this picture with a steaming railway along a body of water an oppressive atmosphere: despite the occasional blossoming trees and the colourful rainbow, albeit in the incorrect order of red-orange-green-blue-yellow instead of red-orange-yellow-green-blue-violet, as well as turquoise watercourses, the black branches, the steam cloud and dark forest area prevent a friendly atmosphere. Was the painting a reaction to his personal situation in exile in Amsterdam, to the defamation as a «degenerate» artist in Germany, to the difficult times of war, despite everything, to express the colourful hope for peace in the sign of the rainbow, in the forward thrust into better times through the railway?

«What matters most to me in my work is the ideality that lies behind the apparent reality. I seek a bridge from the given present to the invisible - ...: «If you want to grasp the invisible, penetrate as deeply as you can - into the visible.» For me, it's always about capturing the magic of reality and translating this reality into painting. ... That may sound paradoxical - but it really is reality that forms the actual mystery of existence! ... I woke up - and saw myself in Holland, in the midst of a boundless confusion of the world. But my faith in a final liberation and redemption from all things that tormented and delighted me was newly strengthened, and calmly I laid my head back into the pillows. To sleep and continue dreaming.» (Beckmann 21 June 1938, translated by art24).

Fig. 5: Max Beckmann, Railway Landscape with Rainbow, Amsterdam 1942, oil on canvas, 55 x 89 cm, privately owned.

Rainbows made of Smoke and Light

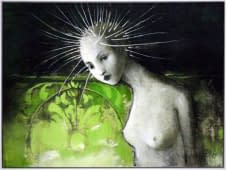

The new beginning of art after the end of the Second World War was to be radical. So radical that Otto Piene (1928-2014), together with Heinz Mack (*1931), founded the artist group ZERO in 1957, which was to literally «start from scratch». Piene, still far too little known today, became one of the most influential pioneers of (kinetic, sculptural) light art. Using smoke, fire, movement and light, he created glowing works in the truest sense of the word. The fact that he found the motif of the rainbow for himself can be seen in many prints, screen prints and gouaches, such as the following example «Lichtbogen (Regenbogen für Hering)» (eng. Lightbow (Rainbow for Hering)) from 1966, which was created as an annual gift for the Kunstverein für die Rheinlande and Westfalen, Düsseldorf and was presumably dedicated to its director Dr. Karl-Heinz Hering. Piene's idea was to create art with reference to human existence. Expressed in the juxtaposition of light and darkness, day and night, life and death. The depiction of the intensely luminous rainbow, its glowing rays intensified with red spray paint against a black background, makes it seem to float slightly and once again becomes the guiding motif of his exploration of sun (light). Piene was not interested in the exact optical reproduction of the rainbow, but in the realisation and visualisation of natural forces.

_800pix.jpg)

Fig. 6: Otto Piene, Lichtbogen (Regenbogen für Hering), colour silkscreen on cardboard, hand-finished with spray paint, 1966, 50 x 70 cm, signed, dated, Epreuve d`artiste. Privately owned.

With the gigantic rainbow for the closing ceremony of the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich, Otto Piene finally created a symbol of peace and made his «Sky Art» famous worldwide.

Part 10 of our blog series explores how the rainbow conquered the remaining decades of the 20th century.